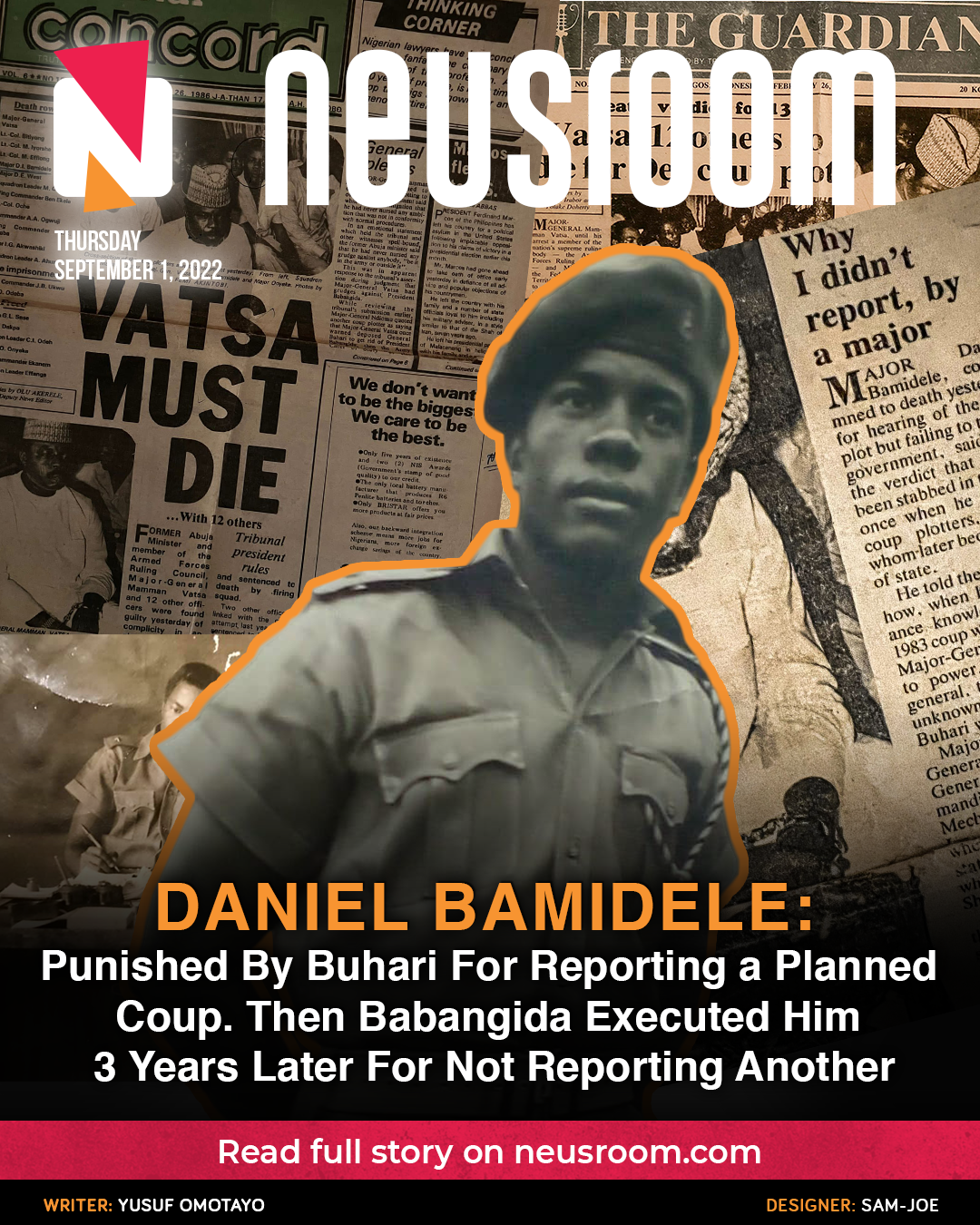

Daniel Bamidele: Punished By Buhari For Reporting A Planned Coup. Then Babangida Executed Him 3 Years Later For Not Reporting Another

Neusroom’s Yusuf Omotayo writes on the story of Major Daniel Bamidele executed for not reporting a coup despite being arrested three years earlier for reporting one.

Daniel Bamidele: The Soldier Executed For Not Reporting A Coup

Written by Omotayo Yusuf for Neusroom

01 September 2022

“Are you interested in my father’s story because another general election in Nigeria is around the corner?”, Remi Bamidele asked me over the phone. “This is what happens during election time. They are always interested in the story of my father, Daniel Bamidele, for political gains.”

I knew I had only a few seconds to convince him I was not using his father’s story for political gains. I could tell he had had similar phone conversations in the past that ALWAYS ended in a dismissal. I did not blame him. I guess if my father was executed by firing squad by the Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida’s military regime when I was 13 and buried in an unknown grave, I would not want his story to be used for political gains.

Bamidele’s crime? He was executed for not reporting a coup in 1986 just 3 years after he was jailed for reporting one.

So in a few seconds, I told Remi Bamidele I write for Neusroom and that we focus on untold stories which encompass historical stories with fresh perspectives, stories of ordinary people who deserve a platform to reach more Nigerians and human-interest stories that deserve the intervention of the government for effective change. I said all these in one breath. I didn’t know if the sweat running down my back was due to apprehension or the late May afternoon heat I was feeling. There was a long silence. I had to check my phone to be sure the Whatsapp call was still connected.

“I will talk to you,” He said finally. His voice was friendlier now and the cold uncertainty was gone. “When do you want us to talk?” I told him Saturday, May 21, 2022, and he agreed. I was about to end the call when he switched to Facetime video. He looked like an older version of his father, Colonel Daniel Bamidele, whom I had seen in several photos. The piercing, questioning eyes were the same except for the full beards of course. While the older Bamidele who was executed at 36 was clean-shaven as required by the military, the 49-year-old who stared at me on the Facetime video from his home in the US had a full beard and looked like the older version of his father. It was quite surreal getting a glimpse of what Daniel Bamidele would have looked like if he had lived up to the age of 49 from his son.

“Do you know my mother was Igbo and met my father during the Biafra war? Do you know my father visited almost all corners of Nigeria? He was more Nigerian than many people who claim to be. I will tell you things about my father you will not find printed anywhere when we talk on Saturday.”

From Biafra war to the Shagari coup: The military life of Daniel Bamidele

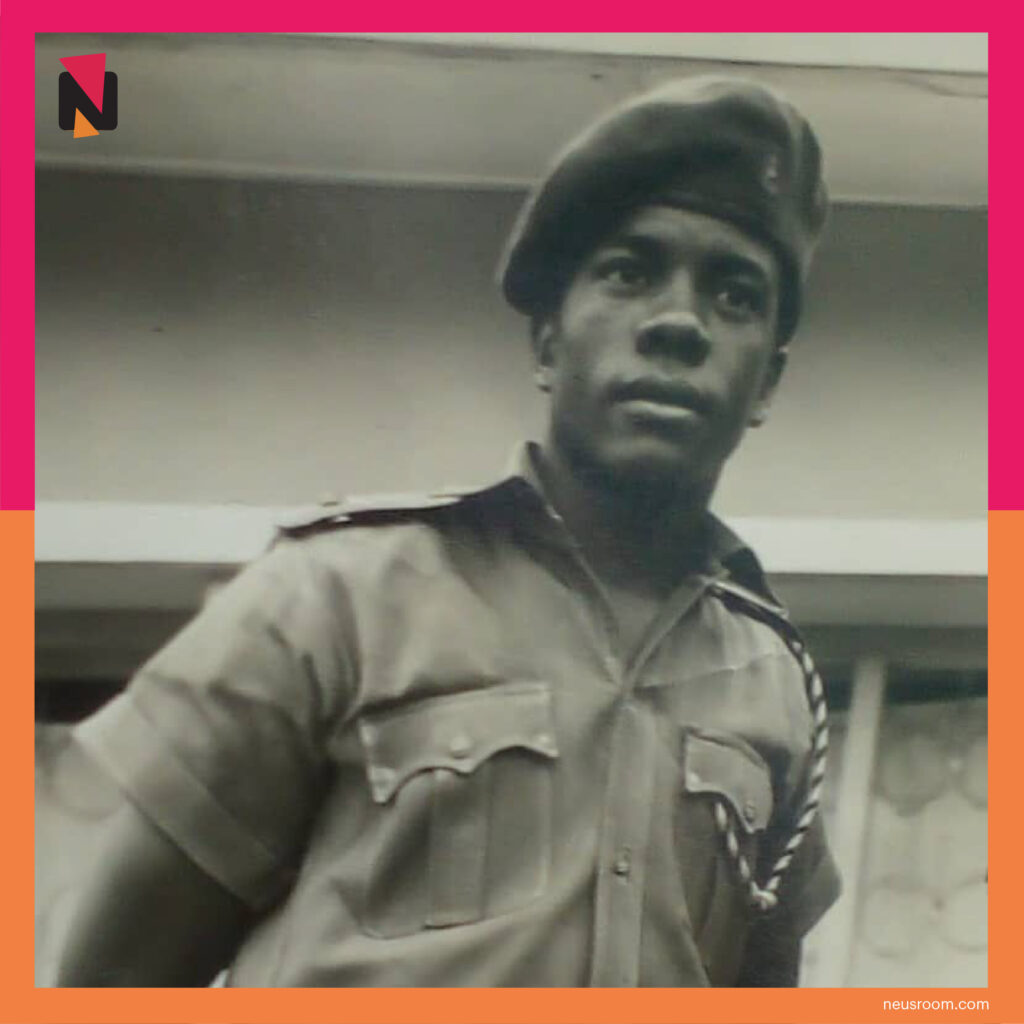

So for the next two days, I went through everything I knew about Major Daniel Bamidele. He was born in 1949 and joined the Nigerian army as a non-commissioned officer in 1968 aged 19 during the heat of the Nigerian Civil War which began a year before he joined. During that period, young men were encouraged and excited to join the military in what they believed was a war to sustain the existence of Nigeria. Despite his relatively young age and lack of experience, he excelled as a soldier in the 12th Commando Brigade 3rd Division initially under the command of Colonel Benjamin Adekunle and later Olusegun Obasanjo.

Daniel Bamidele joined the military aged 19 during the Biafra war before becoming a commissioned officer. Credit: Remi Bamidele

After the war, Bamidele underwent formal military training at the Nigerian Defence Academy and was commissioned on July 29, 1970. He became a military training officer at the academy before being deployed to the 12th Infantry Brigade at Aba as a company commander. There he briefly worked alongside Michael Aker Iyorshe, a Tiv officer who would later rise to the position of Lieutenant Colonel. Iyorshe was a brilliant soldier and won the distinguished Sword of Honor as the best cadet and had the best performance in the Lt. to Captain and Captain to Major promotion exams in his batch.

In 1974, Bamidele went to the UK for military training. Following another commendable result, he was nominated for advanced infantry training at the US Army Infantry course at Fort Benning, Georgia where he graduated with outstanding recommendations. Shortly after, he received a personal letter of commendation from then Chief of Army Staff Lt. Gen. TY Danjuma.

After that, Bamidele attended the junior division of the Ghana Staff College Teshie, where he again attained the highest rank of command during the final military exercise. According to military historian, Nowa Omoigui, from 1976 to 1979 “he (Bamidele) was Grade II Staff Officer in the “G” Branch (operations) at Army HQ. When he returned from Teshie in 1979 he was appointed Grade II Staff Officer for Training at the Nigerian Defence Academy. After completing senior division staff training at Jaji he was made the General Staff Officer 2 (Operations and Training) at the HQ of the 3rd Armored Division in Jos. During this tour of duty, he got nominated for service abroad. In 1982 he was the Operations Officer for the Nigerian Battalion (NIBATT) as part of the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). This was the Nigerian Battalion in Lebanon at the time of the Israeli invasion. Indeed it was the last Nigerian Battalion deployed there – President Shagari pulled Nigeria out of UNIFIL thereafter. Upon his return from Lebanon, Major Bamidele was the operations officer for the 3Div HQ during the border war with Chad.”

In August 1983, Nigeria had a general election and Shehu Shagari was re-elected and sworn-in in October. That same month, Bamidele left Jos for Kaduna to get his Divisional brief for the Chief of Army Staff Conference. There, he heard a rumour about a planned military coup against the new democratic government. According to Omoigui, as soon as Bamidele returned to Jos, he reported the rumour to his General Officer Commanding, then Brigadier Muhammadu Buhari. Unknown to Bamidele, Buhari was involved in the plot to overthrow the government.

A week after he reported the planned coup, Bamidele was arrested and accused of planning a coup against the government of Shagari. He was shocked and he protested his innocence but all fell on deaf ears. In the early hours of one October morning, He was put on a plane and flown to Lagos where he was detained at the Directorate of Military Intelligence at Tego Barracks.

While this was ongoing, Umaru Maikaura Ali Shinkafi who was the head of the National Security Organisation, the precursor to the Department of State Security, had gotten wind of a planned coup against his principal, Shagari and had informed him. Following the arrest of Bamidele, the NSO was informed that a coup planner going around the country to meet with other military officers had been arrested. Although Shinkafi informed Shagari of the arrest of Bamidele, he himself was not convinced but he followed the trial with kin interest.

Bamidele was interrogated by military police while fake witnesses were paraded. He continued to deny plotting a coup or being involved in any plan to remove Shagari from office. After a month in detention, he was finally released on November 25, 1983, after no shred of evidence was found to corroborate the accusation.

The plot to overthrow Shagari however continued as senior military officers in Lagos continued their plan. A week before the coup was carried out, Shinkafi tendered his resignation in what many believe was due to the impending coup. On December 31, Shagari was removed from office and Buhari was made head of state the following day. Buhari in an interview denied his involvement in the 1983 coup saying “…so they could do their Lagos business because I cannot overrun Lagos from Jos, so it is my colleagues then in the military who decided to make me the Head of State.”

Whether Buhari actively participated in the coup to remove Shagari or not, on January 1, 1984, he became the head of state. This came as a surprise to Bamidele who had reported the rumoured coup to his General Officer Commanding. A few weeks after Buhari became head of state, Bamidele’s name was among those listed for retirement and sent to him for approval. Perhaps remembering Bamidele’s ordeal for which he was innocent, he crossed out his name at the last minute and deployed him to Jaji as a directing staff.

Vatsa Conspiracy

Buhari’s military regime lasted for just 20 months before he was ousted in a palace coup in August 1985 and Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida was installed as head of state and placed Buhari under arrest in Benin. He then established the Armed Forces Ruling Council.

In the early morning of December 17, 1985, airforce, army and naval officers were arrested on the suspicion of plotting to overthrow Babangida who had only been in power for four months. This exercise would go on for two weeks as hundreds of uniformed men were rounded up en masse and detained. Among them was Major Bamidele. Major-Gen Mamman Vatsa, a childhood friend of Babangida was accused of plotting and financing the alleged planned coup.

Badamasi Babangida and Mamman Vatsa were childhood friends. Credit: The News

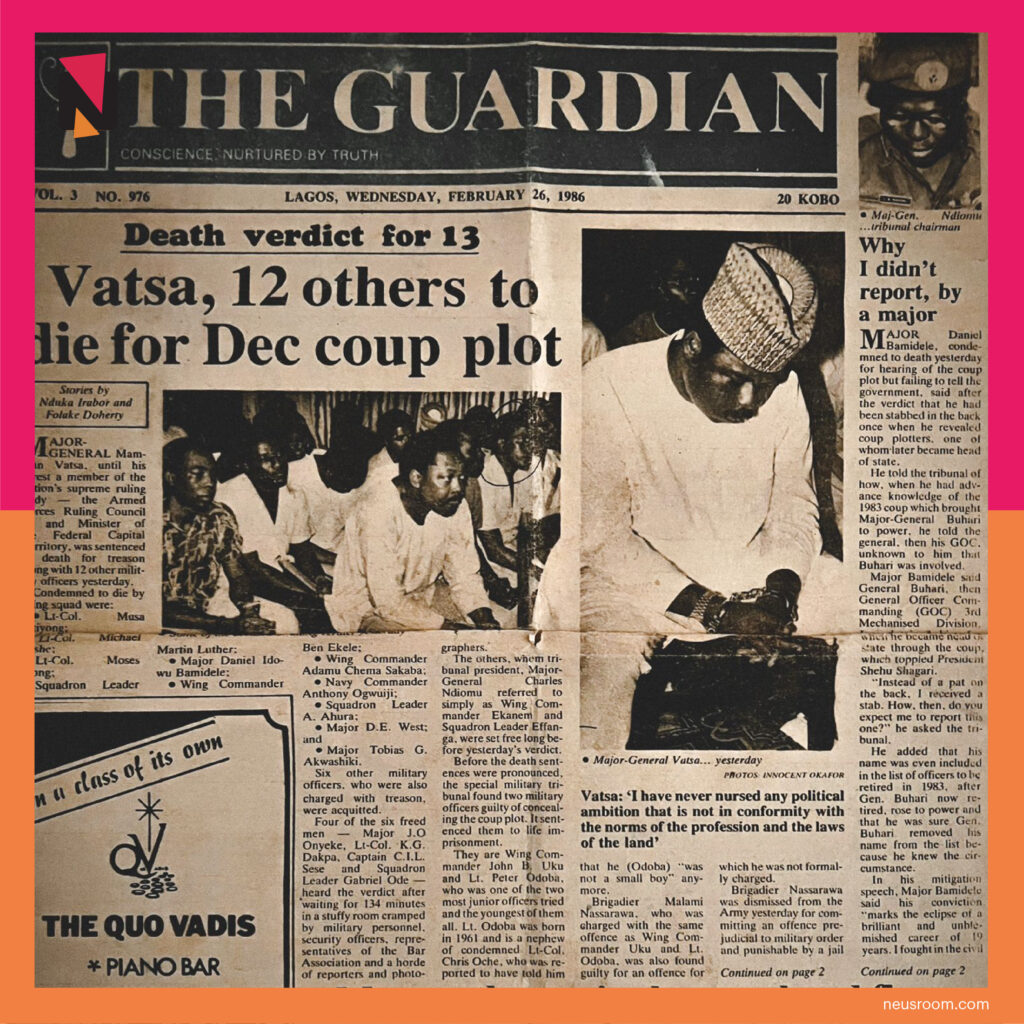

Following a preliminary Special Investigation Panel which was chaired by Brigadier Sani Sami, selected cases were transferred for court martial. On Monday 27th January 1986, the trial began and 17 officers were tried at the Brigade of Guards headquarters located in Victoria Island, Lagos, by a Special Military Tribunal convened by Major General DY Bali who was the then Minister of Defence.

The 17 accused officers were: Major-Gen Mamman Vatsa, Lt. Col. Musa Bitiyong, Lt. Col. Christian A. Oche, Lt. Col. Michael A. Iyorshe, Lt. Col. M. Effiong, Major D. I. Bamidele, Major D. E. West, Major J. O. Onyeke, Major Tobias G. Akwashiki, Captain G.I.L. Sese, Lt. K.G. Dapka, Commander A. A. Ogwiji, Wing Commander B. E. N. Ekele, Wing Commander Adamu C. Sakaba, Squadron Leader Martin Olufolorunsho Luther, Squadron Leader C. Ode and Squadron Leader A. Ahura.

The chairman of the tribunal was Major General Charles B. Ndiomu while other members were Brigadier Yerima Y Kure, Commodore Murtala A. Nyako, Colonel Rufus Kupolati, Colonel Opaleye, Lt. Col. D. Mohammed and Alhaji Mamman Nassarawa (Commissioner of Police). A close friend of Bamidele, Major Akin Kejawa was the judge advocate while the prosecution team comprised Colonel Lawrence Uwumarogie, Major N N Madza, Major B Makanju, and Captain Y. A. Ahmadu.

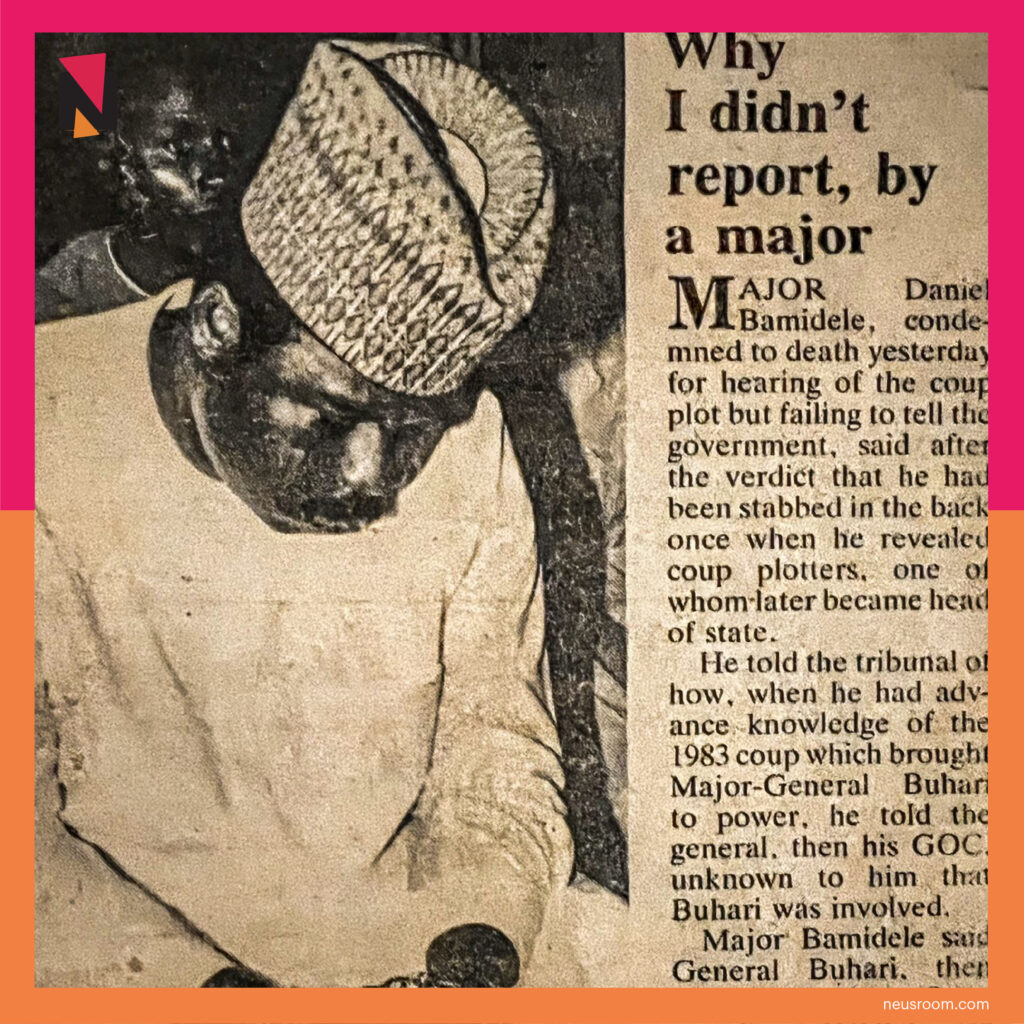

On February 25, 1986, just one month after the trials began, some of the officers were sentenced to death while others were handed life imprisonment. Bamidele was one of those condemned to die. In his speech to the tribunal, he admitted knowledge of a planned coup but denied being actively involved in it. He explained that the reason he failed to notify the military leadership of the coup was that less than three years earlier, he was arrested and detained for reporting a coup and did not want a repeat of the situation. He told the tribunal according to historian, Max Siollun:

“I heard of the 1983 coup planning, told my GOC General Buhari who detained me for two weeks in Lagos. Instead of a pat on the back, I received a stab. How then do you expect me to report this one? This trial marks the eclipse of my brilliant and unblemished career of 19 years. I fought in the civil war with the ability it pleased God to give me. It is unfortunate that I’m being convicted for something which I have had to stop on two occasions. This is not self adulation but a sincere summary of the qualities inherent in me. It is an irony of fate that the president of the tribunal who in 1964 felt that I was good enough to take training in the UK is now saddled with the duty of showing me the exit from the force and the world”

Daniel Bamidele denied participating in the planned coup but was nonetheless executed. Credit: The Guardian

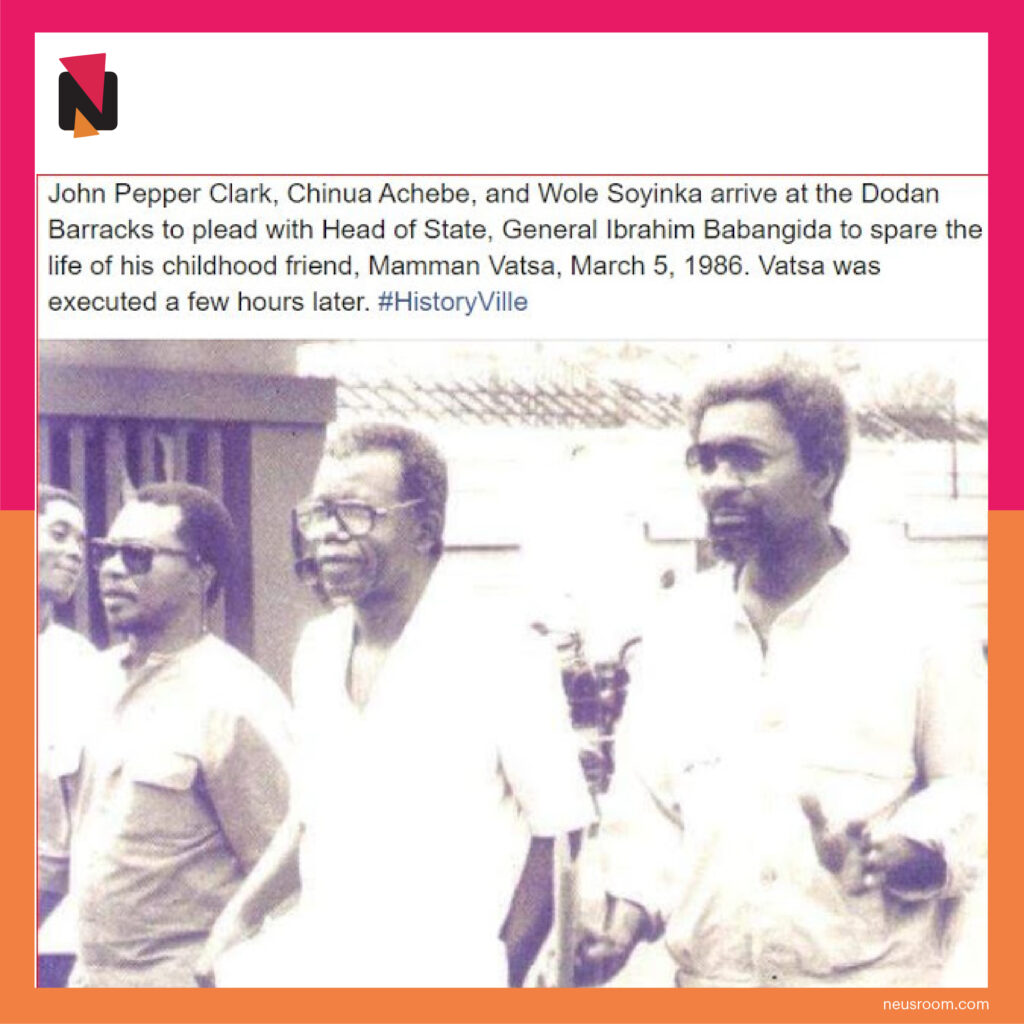

Appeals were made to the head of state, Babangida, to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment but he refused. On March 5, 1986, 10 of the 17 officers were found guilty of conspiracy to commit treason and executed by firing squad. They were: Vatsa, Bitiyong, Oche, Iyorshe, Bamidele, Ogwiji, Ekele, Sakaba, Luther, and Ahura.

There have been conflicting reports about what happened after the execution. While some claimed the officers were buried in an unmarked mass grave, others say acid was poured on the bodies of the 10 officers to destroy them. What is indisputable is that there is no official information on what happened to the bodies.

According to Omoigui, “Many of the officers executed were of the highest calibre in the military, had required years of expensive training to produce, and were looked upon as models of professional military excellence…In furtherance of the climate of suspicion between the regime and the core military, some military services were defanged. The systematic destruction of the Air Force, for example, started with those executions.”

Writers JP Clark, Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka protested against the death sentence. Credit: Historyville

Conversation with Remi Bamidele

My conversation with Remi Bamidele was supposed to be for thirty minutes. When I called him that Saturday evening, May 21 he was in the parking lot of an airport ready to catch a flight. The conversation ultimately extended to more than one hour and it still felt as though it was not enough. He was as excited as I was to hear his story. Although I did not ask him this, I was almost certain that he had not had the chance to express himself on this topic without holding back. I was a willing listener in his cathartic journey to find an answer to his most important question: “Where is my father buried?” I did not have an answer to it.

“My father was born in Port Harcourt to Yoruba father and an Igbo mother from Igbo state. My father fought during the Biafra war under the command of Benjamin Adekunle nicknamed ‘Scorpion’”, Remi said proudly, “My mother was an Igbo nurse during the war and she took care of injured soldiers and refugees. It was a year after he joined the army that my father met my mother in 1969 in one of the refugee camps.”

According to Remi, the two of them fell in love and Bamidele encouraged his wife to go with a military truck to Lagos. She insisted that she would only go if 20 other people in the camp whom she had made friends were allowed to go with the truck which Bamidele agreed to.

“After the war ended in 1970, my father returned to Lagos where he met my mother, asked her to marry him and she agreed and they got married in Obalende. A year later, he was posted to Potiksum.”

Bamidele’s family were initially not in support of his decision to marry an Igbo woman. It was the period shortly after the war and ethnic suspicion still lingered. When his mother got pregnant in 1972, Bamidele’s family were certain she would give birth to a female child and grumbled about how much they would have preferred a son. But his father made it clear that he did not care. He loved his wife and stood by her.

“My mother named me Remilekun or Remi for short which meant ‘dry my tears’ because when she delivered her child and it was a boy, she felt elated that finally, her husband’s family would accept her. She gave birth to two more children, one male and one female.”

According to Remi, his father’s work as a soldier meant the family lived in military barracks while the children attended military schools and so their social circle was made up of wives and children of military men.

“My father loved his family but he had no patience for stupidity. As his first son, more was expected from me. He was high-handed when he needed to be and was as well gentle. Despite the fact that he was constantly travelling around the country and outside of Nigeria for training and deployment, he made sure we were happy. Because of his absence, my mother had to be a full-time housewife so she could always be there for us.”

When Bamidele was arrested in December 1985 on the allegation of plotting a coup, Bamidele said the family were optimistic that he would be released. After all, he was arrested in 1983 and released months after.

“I remember when my father was released in 1984. I was 11 then but I remembered he returned with an untreated gun wound in his leg. Every morning, my mum would treat it with warm water and we will watch his leg bleed.”

When military officers arrived to arrest Bamidele in 1985, he was spending time with his children in their military quarters in Jaji. His wife was in Lagos then to check the progress of the family house that was being constructed at Toyin street in Ikeja.

“We were home that day when soldiers stormed our compound and created a formation close to our door with guns drawn. An officer using a megaphone ordered my father to come out and surrender. My father knew something was wrong when he saw military combatants in his house. He wore his bulletproof vest under the white kaftan he always wore anytime he was home and not in uniform. Eventually, he stepped out and was arrested without incident.

“My mother was not aware of her husband’s arrest until she boarded the military plane from Lagos coming to Kaduna which wives of military officers were allowed to use and overheard other women whispering in Hausa and pointing to her that her husband had been arrested for plotting a coup. They did not know my mother who was born and grew up in Kaduna understood Hausa. So she approached the female pilot who was from Akwa Ibom and confirmed that my father had truly been arrested.”

Shortly after Bamidele’s arrest, the family was kicked out of the military residence. His wife and two children moved to Lagos while Bamidele remained in Kaduna at the Command school in Jaji.

“We were cast away like outcasts. My mother’s only social circle was made up of wives and relatives of military men and after her husband’s arrest, no one wanted to have anything to do with a coup plotter. It was a big stain. That she was an Igbo woman who understood Hausa did not help her cause. The privileged free military flight ended. All her friends left and things became difficult financially because she was not working before her husband’s arrest”

On Wednesday, March 5 1986, Bamidele was in class when military men drove into his school in land rovers. Their presence there was not a surprise. The 13-year-old was however baffled when his name was called out and was asked to pack his things from the hostel.

“That was the last day I saw my classmates. I was driven out of the military school and taken to Lagos. I saw a lot of people in our house with my mother inconsolable. That was how I found out about my father’s execution. They killed a just man and to date, did not tell us where his body is. We have not had closure. How can I not know where my father is buried? How can a man who believed in one Nigeria and loved his country be buried like a dog without a grave? I am a Yoruba man and I cannot point to my father’s grave. Why?”

The execution of Vatsa, Bamidele and 8 others changed the Nigerian military according to historians. Credit: National Concord

At this point in our conversation, the younger Bamidele burst into tears, his body racking with each sob, saying the family has reached out to the leadership of the military to exonerate their father and clear his name.

“I want Nigeria to know what the military did to an honourable man. I want them to know how families were left to suffer after the life of an innocent man was wasted. We are not asking for money or financial compensation. We just want his name cleared and the location of his body revealed to us.”

Bamdele’s execution came as a shock to his family who thought the whole trial was a charade and like the first one, he would be found innocent and released. Bamidele himself at first felt confident that he would be cleared. In a letter he wrote to his friend and confidante, Colonel Kejawa, from detention at Ikoyi prison, Bamidele apologised for the embarrassment the arrest must have caused him but reiterated that he had nothing to do with the planned coup. He revealed to his friend in the letter that although he was certain that a trial will take place, he was sure of being cleared and even promised to voluntarily resign from the army after his release due to his soiled reputation. Little did he know he would not see his wife and three children again.

Shortly before his execution and when it became certain to him that there was going to be no reprieve,, Bamidele scribbled a will on a scrap of paper highlighting the properties he owned. He smuggled it to one of the prison wardens who agreed to deliver it to his wife.

“After my father died, things became very difficult for the family. My mother did not have a job so we watched as she sold some of our belongings to raise money for food and upkeep. The things we used to take for granted suddenly became luxury. We became victims of the execution. My father’s family withdrew their support and all the people we called our friends perhaps for fear of the military regime deserted us. We suffered alone”

According to Remi, his mother at a point had to crawl back to the military to ask for work so as to raise more money to continue to send her children to school. Ultimately, she was given a contract to make uniforms for officers.

“The tragic and untimely death of my father messed up the family. My younger sister and I never remained the same mentally. Only my brother who was still young when the whole thing happened escaped unscathed. The rest of us were dealt mental blows.

“I went to Spain at the invitation of an uncle for school but on getting there, he did not come to pick me up and so for months, I slept on the street homeless. And then I was exposed to drugs. I had to scratch my way from the bottom to get to where I am today.

“My mental health is a mess. I cannot keep a family and I do not think I will be at rest until I find answers to my questions. I have not lived my life up to expectation because my father achieved more at his age than I have.”

For many Nigerians, the execution of the 10 soldiers in 1986 is just a piece of history, For Remi and other members of his family, it has had long-lasting effects that cannot be erased. He has written to the Nigerian Army to inquire about the burial site of his father but has gotten no response.

Remi said in 2021, he received a message from an old military officer who claimed to be one of the soldiers selected to execute the 10 soldiers convicted of coup plotting. He was an old man and was embarking on a sort of soul-cleansing.

“He told me the men when singing the Nigerian national anthem when they were executed”, Bamidele said with renewed tears in his eyes. “Thanks for letting me cry, Yusuf”, he said touchingly. “It hurts me that Nigeria lost a lot. They were some of the finest well-trained brilliant crops of officers we had. The military has never remained the same since then.”