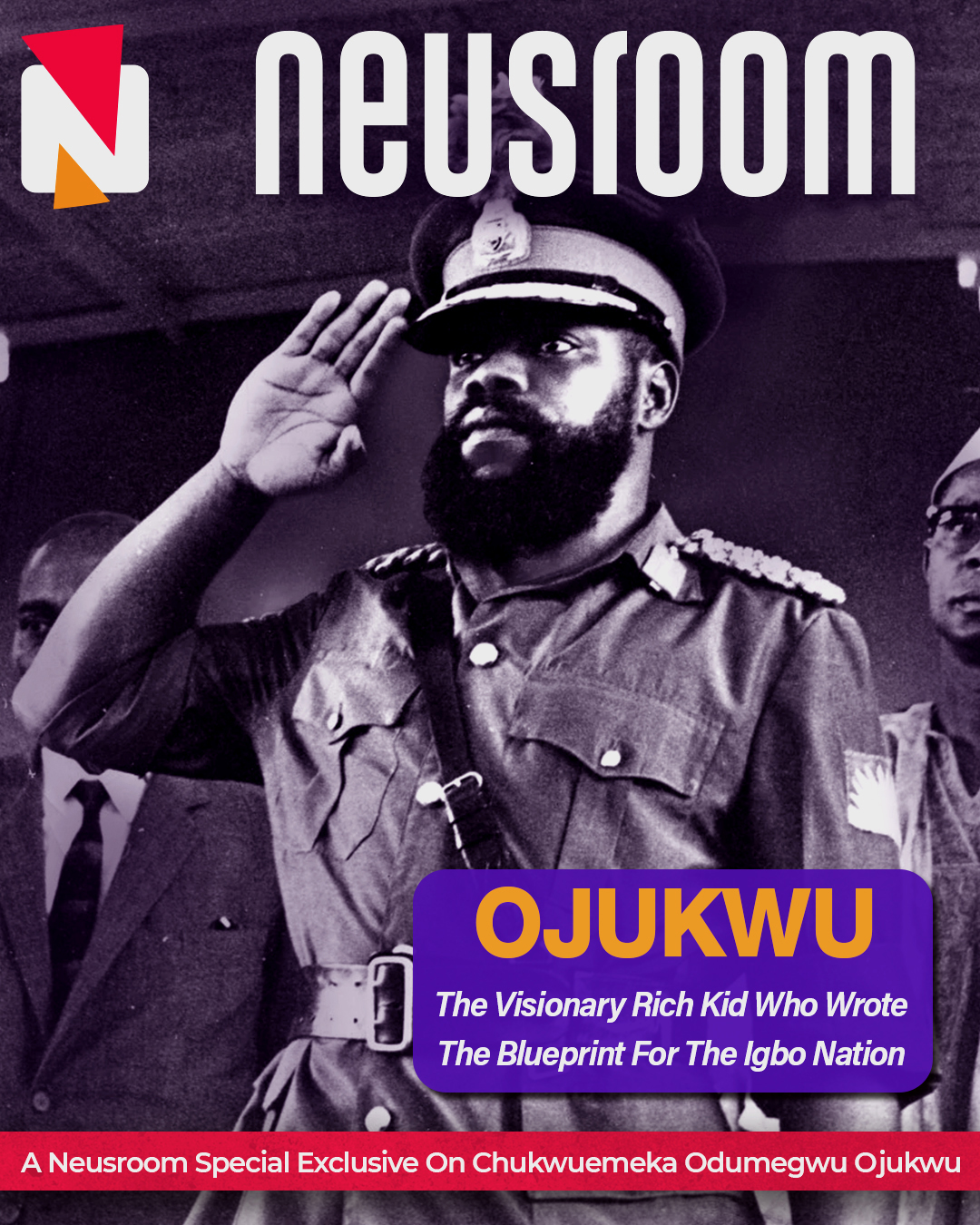

Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu – the visionary rich kid who wrote the blueprint for the Igbo nation

A Neusroom special feature on Biafran warlord Chukwuemeka Ojukwu.

Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu – the visionary rich kid who wrote the blueprint for the Igbo nation

Written by Michael Orodare for Neusroom

15 August 2020

In the past two decades, the Nigerian government has battled the resurgence of a pocket of secessionists advocating for the break away of Eastern part of Nigeria. Ralph Uwazuruke of the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) led the advocacy in the early 2000s and recently the status of Nnamdi Kanu of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) as the new poster boy of Biafra movement has been simmering.

What is distinct about Kanu and Uwazuruike is their ‘eye for an eye’ approach to achieve their aim, and the cult-like followership they enjoy within the youth demography. But their power and influence pale when compared to one key person in the history of the region – Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, who declared the secession of the East from Nigeria in 1967 and announced the Republic of Biafra that tipped the country into a 30-month civil war from July 7, 1967 to January 15, 1970, with an estimated casualty of three million people.

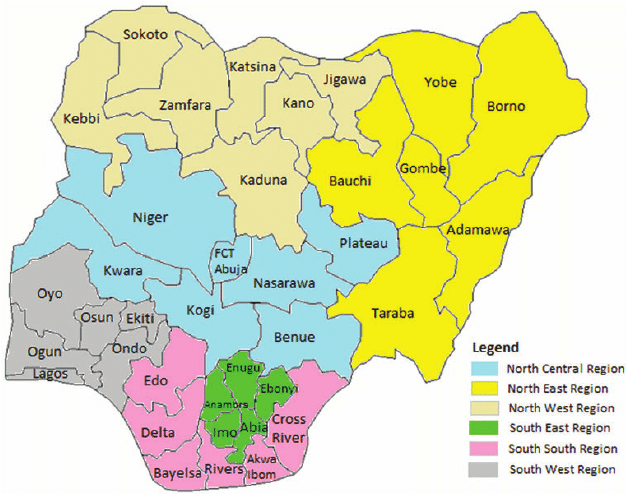

The Igbo people, with an estimated population of 40 million, inhabit the south eastern part of Nigeria – Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo states, as well as related areas like Delta, and Rivers. But the war was not only about the Igbos, it also involved minority ethnic groups – Ijaw (in Bayelsa, Delta and Rivers State), Ogoja, Ibibio, Efik in modern day Cross-River and Akwa Ibom state.

The Biafra War was the gory result of two coups in the space of six months, just six years after Nigeria’s independence from colonial rule on October 1, 1960. The first coup, in January of 1966, is widely believed to be an attack against northern leaders by Igbo military officers led by Major Kaduna Nzeogwu. This culminated into a counter coup in July 1966 by the northerners.

The counter coup led to pogroms in which an estimated 30,000 Igbos living in the North were reportedly killed. The killings led to a mass exodus of Igbo people from the North and other parts of Nigeria to the Eastern Region. This exodus was followed by a declaration by Ojukwu in 1967 that the Igbos would secede from Nigeria. The declaration was met with stiff opposition from the Nigerian government with the backing of the British government who blocked the Biafra secession with military forces over fears that the country that had just been granted independence was disintegrating.

Despite the forceful blockage, the Biafran agitators were more desperate about moving out of Nigeria where Ojukwu said they “felt unwanted” than Nigeria was prepared to accept. Force met with brutal force and the result was beyond catastrophic. In his book – ‘There was a country’ – his account of the civil war released 42 years after the war, award-winning novelist Chinua Achebe, portrayed the Nigerian government as ruthless in its suppression of the Biafran movement. Achebe himself played a prominent role in the Biafra agitation and became Biafra’s communications minister. In 1969 he helped write the official declaration of the “Principles of the Biafran Revolution.”

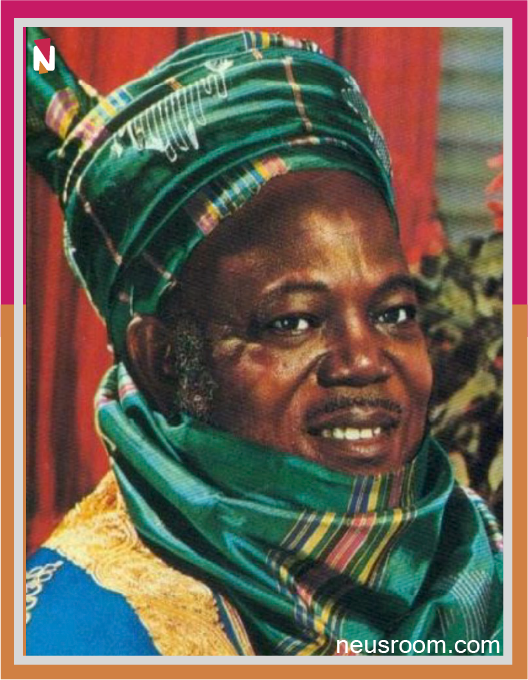

The man Ojukwu and how he became the voice of Biafra

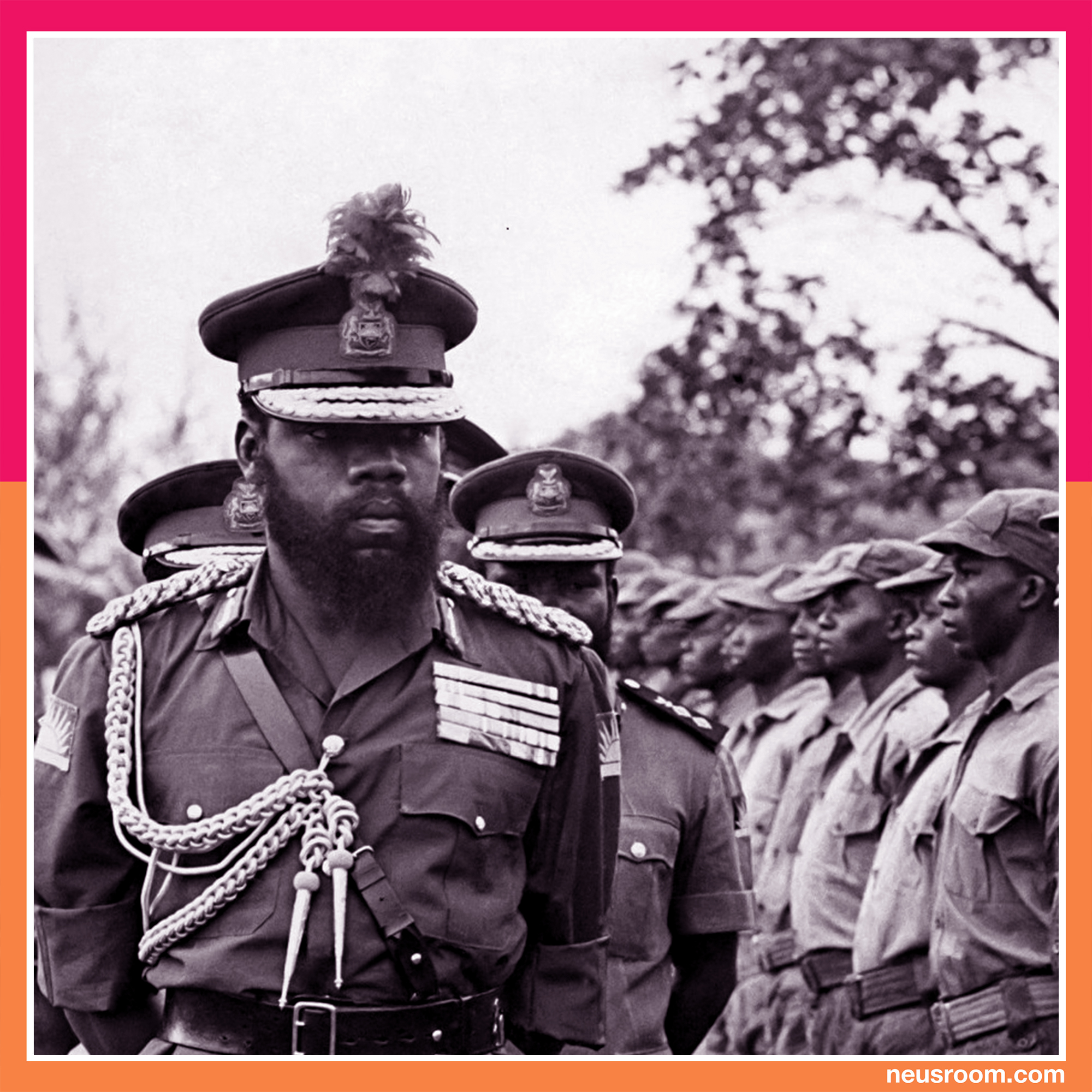

Ojukwu inspects the Biafran troops. Photo: weaponsandwarfare.com

Ojukwu was a United Kingdom-educated soldier who had access to political power at the early stage of his life like many of his contemporaries who took over the affairs of Nigeria after the departure of the British colonialists.

His father Sir Louis Odumegwu-Ojukwu was one of the richest Nigerians of the 20th Century. He was a transport magnate who was said to have offered his Rolls Royce to chauffeur Queen Elizabeth II around during her visit to Nigeria in 1956.

Born November 4, 1933 in Zungeru, Niger State, Chukwuemeka Ojukwu lived in affluence and had the best education at top institutions in Nigeria and overseas – King’s College, Lagos, Epsom College, Surrey, England and the University of Oxford, UK where he bagged a degree in History in 1955, aged 22.

On his return to Nigeria, he was expected to join his father’s flourishing business but he chose to look elsewhere by joining the Eastern Nigeria administrative service. In 1957, he decided to join the Nigerian Army, becoming one of the first set of Nigerian graduates to do so. His promotion was rapid, largely due to his academic background.

By 1963, he was already a Lieutenant Colonel. Surprisingly that was the last ranking recorded for him in the Nigerian Army. When he received his military pension in 2008, he complained that he was paid as a Lieutenant Colonel (his last rank before the civil war) rather than as a General, his rank in the Biafran army. American writer, Kurt Vonnegut, who visited Biafra with other American writers during the war, on Ojukwu’s invitation, described Ojukwu as a calm, heavy man and a chain smoker.

How the civil war started

Some southern military officers led by Major Kaduna Nzeogwu, Emmanuel Ifeajuna, Adewale Ademoyega, Christian Anuforo, Donatus Okafor, Humphrey Chukwuka and Timothy Onwuatuegwu, who were dissatisfied with the alleged northern domination and discrimination in the military and public service, the economic woes, social injustice and corruption in the country, orchestrated the January 1966 coup.

In his memoir, ‘Why We Struck’, Ademoyega, one of the plotters, explained that “Our enemies are the political profiteers, the swindlers, the men in high and low places, that seek bribes and demand 10%; those that seek to keep the country divided permanently so that they can remain in office as ministers or VIPs.”

“Once they were so uplifted by the society, they became solely and wholly motivated to use every opportunity to lift their immediate family out of the level of the masses into the privileged class and also to keep themselves perpetually in that class and totally abandon the masses.”

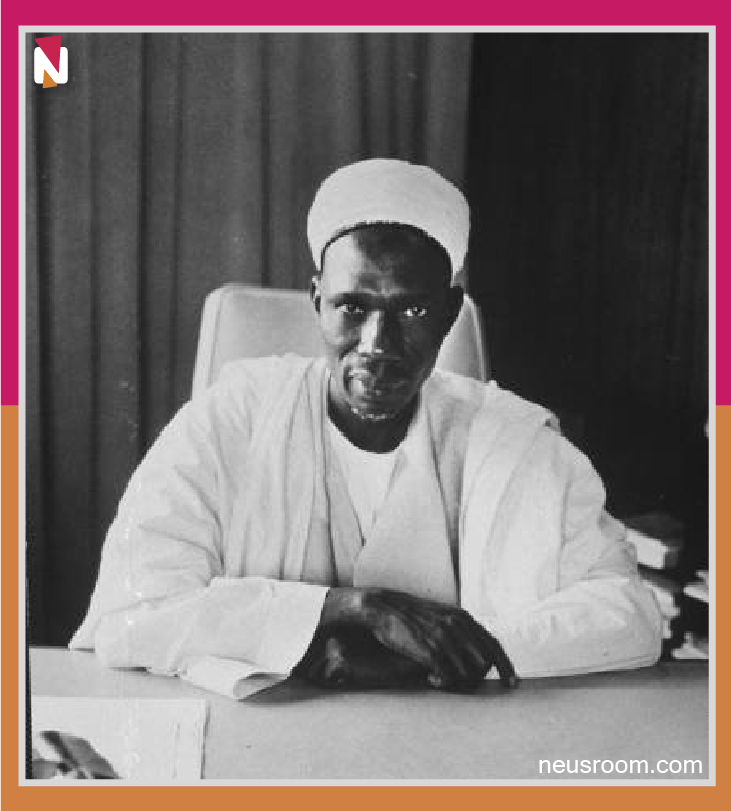

Tafawa Balewa, Nigeria’s former Prime Minister was one of the casualties of Nigeria’s first military coup in January 1966. Photo: Wikimedia.

He listed social injustice, mass illiteracy, the economic order as some of the societal ills his group planned to correct with their revolution.

Ademoyega said if their planned revolutionary system had succeeded, “Nigeria would have emerged as a country with a very strong legs to stand upon… And we would have started to perform like men who have a destiny. This was our stance. We cherished the ideology and discussed it like brothers very often at the Officers’ Mess and in working units.”

The coup brought Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi to power as the Head of State and Ojukwu was appointed the military governor of the Eastern Region at age 32.

Ironsi’s emergence as Head of State, the origin of the coup plotters (mostly Igbo officers and a Yoruba officer), as well as the tribe of the casualties of the coup fuelled belief that the coup was an Igbo coup, and this narrative has remained part of Nigeria’s history more than 50 years after the coup even though Ademoyega denied this in his memoir before his death.

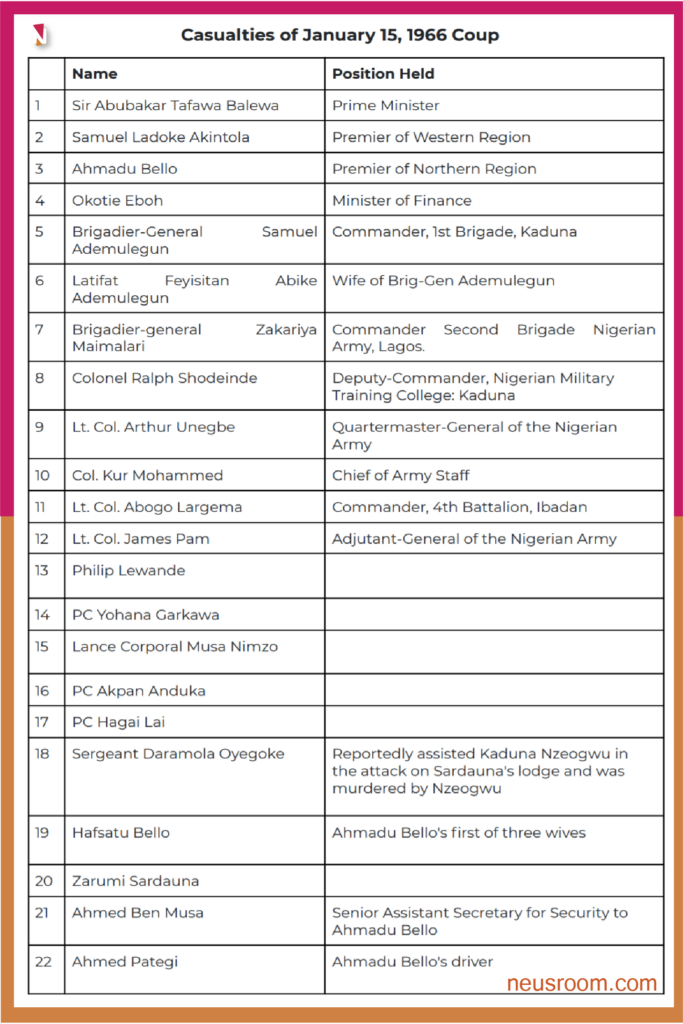

The casualties of the coup include Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa, Premier of Northern Region, Ahmadu Bello; his Western counterpart, Samuel Akintola; Finance Minister Festus Okotie-Eboh (Itsekiri), Brig. Samuel Ademulegun, Lt. Col. Arthur Unegbe (Igbo) and others.

Casualties of the January 1966 coup.

Since many northerners believed that the January 1966 coup was an Igbo coup executed by Igbo officers to dominate the federation, northern military officers executed a bloody counter coup on July 29, 1966. Murtala Muhammed (who later became a military head of state), Theophilus Danjuma, and others masterminded the coup.

The counter coup brought in Lt. Colonel Yakubu Gowon as Head of State and the mass killing of Igbo people that followed marked the beginning of animosity between the northern and the eastern region which quickly snowballed into the Biafran declaration.

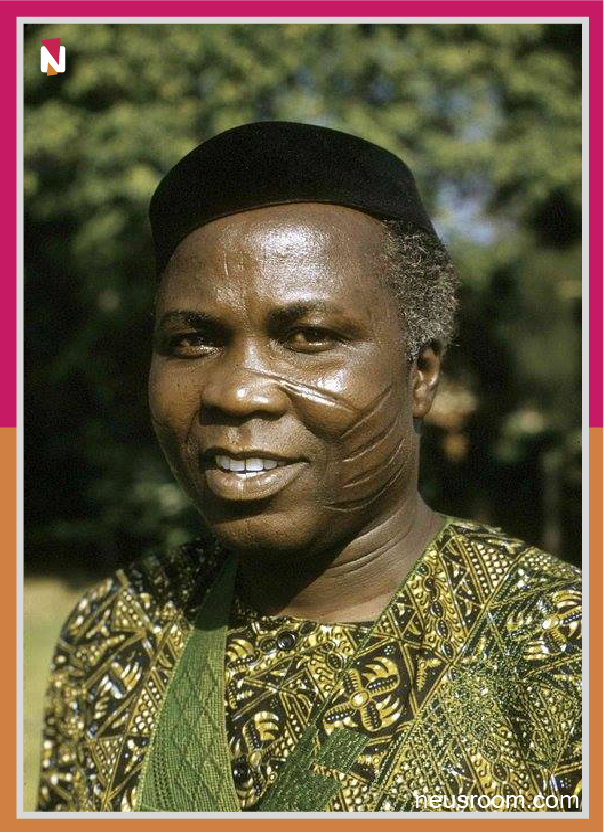

Samuel Akintola, the Premier of Western Region was murdered in the January 1966 coup. Photo: HiztoryBox.

When the counter-coup came six months later, Ojukwu refused to step down as the governor of the Eastern Region, the events of that year thrust the 33-year-old into the leadership role. A peace talk in January 1967 – the Aburi Accord in Ghana – failed to pacify the already agitated Easterners who were hellbent on breaking away from Nigeria. On May 30, 1967, Ojukwu, who had the backing of the Igbos, declared independence for the 29,000 square-mile Eastern region covering 11 provinces in the present day Abia, Enugu, Ebonyi, Imo, Anambra, Rivers, Bayelsa, Cross River and Akwa Ibom state.

The Igbos launched the Biafran flag featuring a golden half rising sun on a horizontal tricolour of red, black and green. The Naira was no longer valid as the medium of exchange in the region and a new currency – the Biafran Pound, was introduced on January 29, 1968.

A pro-Biafra protester holds a Biafran flag at a rally in Abuja, Nigeria. Photo: Reuters/Afolabi.

The golden sun on the Biafran flag influenced the title of award-winning Nigerian writer, Chimamanda Adichie’s novel – ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’, her account of the civil war. The declaration of the Biafra Republic set the motion for a civil war that lasted for almost three years. While the war raged, the Biafran nation starved, all the roads and ports leading to the region were blocked by the Nigerian government, making it difficult for aid to get to the region. This led to mass starvation, kwashiorkor and mental illness among children, women and the soldiers.

Ahmadu Bello, the Sarduana of Sokoto and Premier of Northern Region, his wife and aides were killed in the January 1966 coup. Photo: Leadership.ng

The Biafra War soon attracted massive international attention as the horrendous images of victims of the war dominated international media and roused sympathy from the rest of the world. People like American singers – Joan Baez, John Lennon, political activist Martin Luther King and late American writer, Kurt Vonnegut rose to mobilise international responses to the tragedy. Vonnegut described Ojukwu as Biafra’s George Washington.

He wrote: “Biafra had a George Washington — for three Christmases and a little bit more. He was and is Odumegwu Ojukwu. Like George Washington, General Ojukwu was one of the most prosperous men of his place and time. He was a graduate of Sandhurst, Britain’s West Point… we spent an hour with him. He shook our hands at the end. He thanked us for coming.

“If we go forward, we die,” he said. “If we go backward, we die. So we go forward.”

The Biafran one pound note introduced in January 1968. Photo: Biafraland.com

When the war ended in 1970, three million Biafrans had died, while 100,000 casualties were recorded on the Nigerian side. According to Chinua Achebe, Igbos weren’t mere casualties of war, but victims of calculated genocide.

The Blame Game

Ojukwu and Gowon: driven by ego that made them miss several opportunities to reach a compromise. Photo: Biafran.org

Neither the Nigerian government nor the Biafran forces led by Ojukwu have taken responsibility for the high casualty from the civil war which Achebe described as genocide against the Igbos. The Gowon-led government declared “no victor, no vanquished”. When Gowon appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Oputa panel) set up by the government of ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo, in 2002, he apologised for the massacre of about 500 men in Asaba, but Col. IBM Haruna, who led the brutal killing said: “As the commanding officer and leader of the troops that massacred 500 men in Asaba, I have no apology for those massacred in Asaba, Owerri, Ameke-Item.

I acted as a soldier maintaining the peace and unity of Nigeria…If Yakubu Gowon apologized, he did it in his own capacity. As for me, I have no apology.

Ojukwu also said he would not take responsibility and claimed he took the right step to protect his people. He said:

“Responsibility for what went on – how can I feel responsible in a situation in which I put myself out and saved the people from genocide? No, I don’t feel responsible at all. I did the best I could. “At 33 I reacted as a brilliant 33-year-old,” he said. “At 66 it is my hope that if I had to face this I should also confront it as a brilliant 66-year-old.”

Many writers have posited that Ojukwu and Gowon, who were 33 and 32 years old respectively, were driven by ego that dragged the war for too long.

Youthful exuberance? We may not be able to say. Ojukwu was said to be a rank higher than Gowon in the Nigerian Army and he believed Gowon was not the appropriate person to lead the country at the time he became the Head of State.

Both men never published any books detailing their accounts of what happened.

“There are a number who believe that neither Gowon nor Ojukwu was the right leader for that desperate time, because they were blinded by ego, hindered by a lack of administrative experience, and obsessed with interpersonal competitions and petty rivalries,” Achebe wrote in his last novel – ‘There Was a Country’.

Brig-Gen. Samuel Ademulegun and his wife, Latifat, were murdered by the mutinous soldiers in the presence of their six-year-old daughter, Solape. Photo: CityPeople.

compromise could have saved the day.”

In 1989, Ojukwu justified the concept of Biafra as a line drawn for a persecuted people to have a beacon of hope.

“A line drawn so that a fleeing people can at least hope that once they cross it, they have arrived at a goal, a line drawn so that a hated and persecuted people can at least know that once they reach there, they would have love and succour,” he said.

Ben Lawrence, a former Editor of Daily Times newspaper who witnessed the civil war, told Neusroom in an interview in February 2021 that he believes the war was caused by the youthful exuberance of Ojukwu and Gowon.

“I was about 30 and I saw the war on both sides. The war looks to me now, uncalled for. It was the youthful exuberance of Gowon and Ojukwu, not necessarily the older people that caused the war. Yes, the Igbos were wronged, but they were very tactless themselves. After the first coup in 1966, which was genuine, they didn’t behave well,” Lawrence said. “I learnt Ojukwu’s father died because of the war. He was never in support and he couldn’t stand it.”

He also added that Nnamdi Azikwe never supported the war. Asked who were the prominent easterners who backed Ojukwu to go to war, Lawrence said:

“If you were an easterner, you would have supported Ojukwu at that time because of what happened. Alvan Ikoku and Eyo Ita were Ojukwu’s chief supporters. Eyo Ita was one of the foremost nationalists Nigeria produced. He was an Efik man; he was not an Igbo man, yet he supported it. In fact, he was the leader of the civilians followed by Alvan Ikoku.”

In a statement on January 16, 1970, he said “Biafra was born out of the blood of innocents slaughtered in Nigeria during the pogroms of 1966.”

The Map of Biafra. Photo: Facebook/Radio Biafra

Ojukwu had claimed that the Easterners were treated as second class citizens in Nigeria with so much hatred. “The problem with Nigeria has always been how to accommodate these very energetic Igbo. Under the British, it was how to accommodate the uppity Igbo,” Ojukwu said. “Then after independence, it was how to accommodate these Igbo who do not stay in their area but wander around everywhere. That is why it was easy to think that the answer was to kill them off and prevent them from ever coming back.”

How the war ended

In 1970, Ojukwu handed over authority to Lt. Col. Philip Effiong, his second-in-command, and escaped from the Eastern Region to live in exile in Côte d’Ivoire, one of the four African countries that recognized Biafra. Others were Zambia, Gabon and Tanzania.

Although the move has been described by many as cowardice, Achebe, Vonnegut and many other scholars believe his decision was in the right order.

Achebe said if Ojukwu had stayed in Nigeria, Gowon would have been less magnanimous and conciliatory towards Igbos after the war. “I found him perfectly enchanting. Many people mock him now. They think he should have died with his troops. Maybe so,” Vonnegut wrote. “If he had died, he would have been one more corpse in millions.”

A week after he left Nigeria, Effiong negotiated the surrender of the secessionist forces, and on January 15, the day that the surrender documents were signed in Lagos, Biafra ceased to exist. Ojukwu issued a statement from exile saying: “Biafra will ever live not as a dream but as the crystallization of the cherished hopes of a people who see in the establishment of this territory a last hope for peace and security. Biafra cannot be destroyed by mere force of arms.”

Nigeria after Biafra War

After the integration of Igbos into the Nigerian society in 1970, the Nigerian government gave them a £20 flat fee in exchange for the Biafran pound. Despite the reintegration, the mistrust and discrimination which led to the war still exist. The Igbos are still faced with mistrust, economic and political discrimination.

Since the civil war ended 50 years ago, the Igbos have been largely excluded from power and no Igbo man has become Nigerian president.

“None of the problems that led to the war have been solved yet,” Ojukwu said. “They are still there. We have a situation creeping towards the type of situation that saw the beginning of the war.”

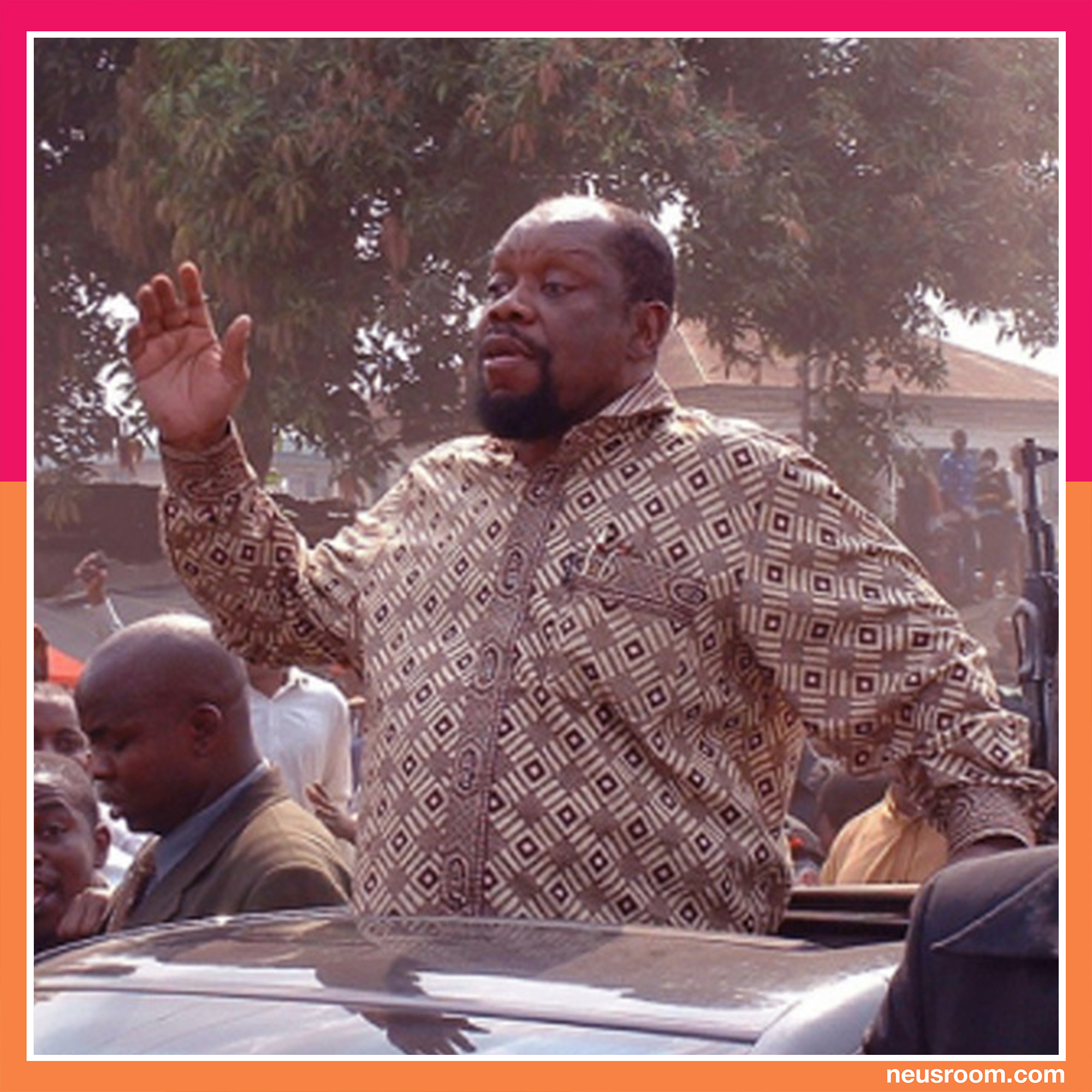

Ojukwu made a triumphant return to Nigeria in 1982 after he was pardoned by President Shehu Shagari. Several biographers, including Achebe and Vonnegut, have described him as a gifted orator, charismatic but highly controversial leader. Although he never achieved the secession he sought which led to the death of an estimated three million people, the foundation he laid for the actualisation of the dream lingers.

Map of Nigeria showing the 36 states and the FCT. Photo: Researchgate.net

Many have argued that Biafra has become an ideological concept that could be difficult to abolish. Generations after Ojukwu have seen it as an integral part of the Igbo history and believe they have to carry on with Ojukwu’s legacy to actualise the dream of an Igbo nation.

Ojokwu’s Personal Life

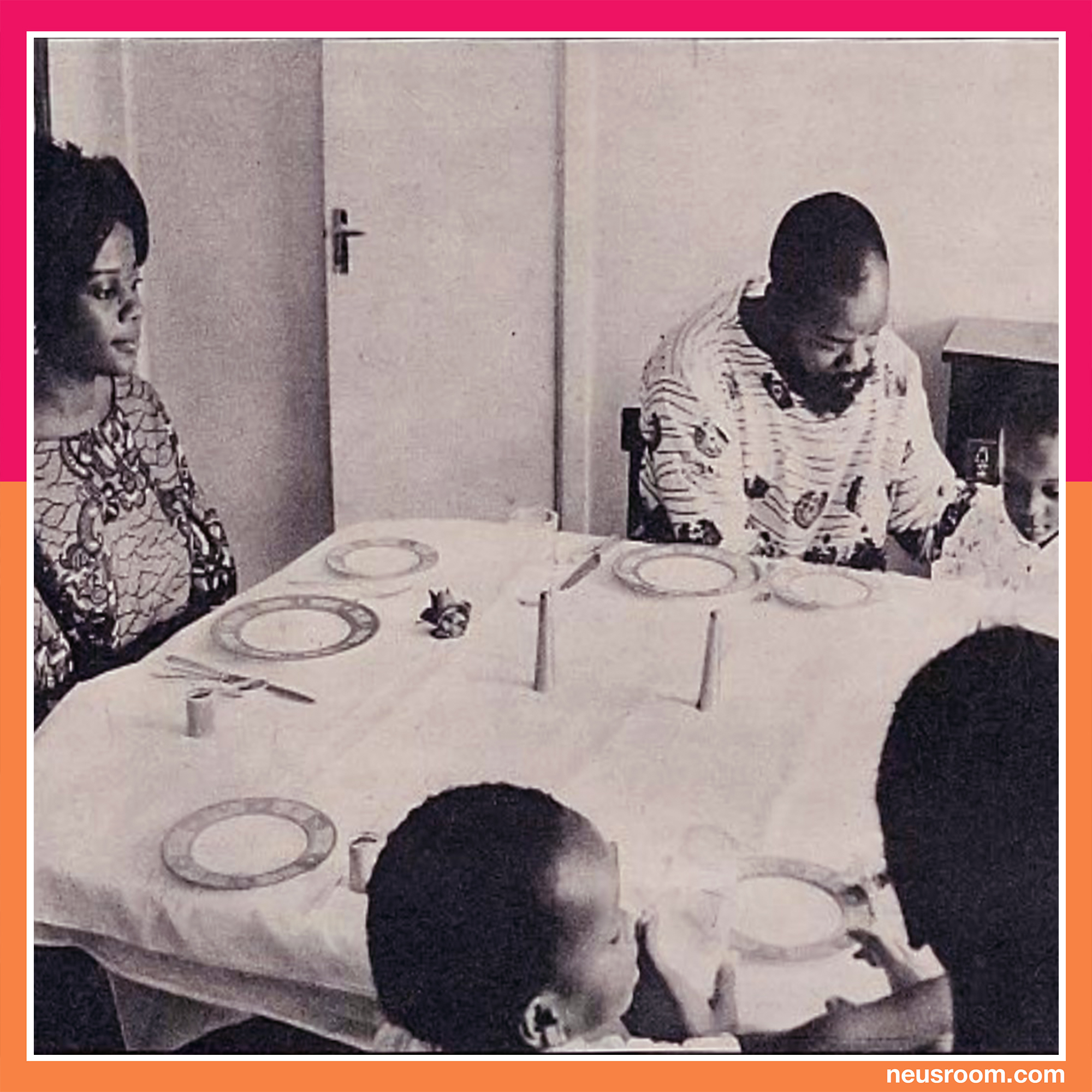

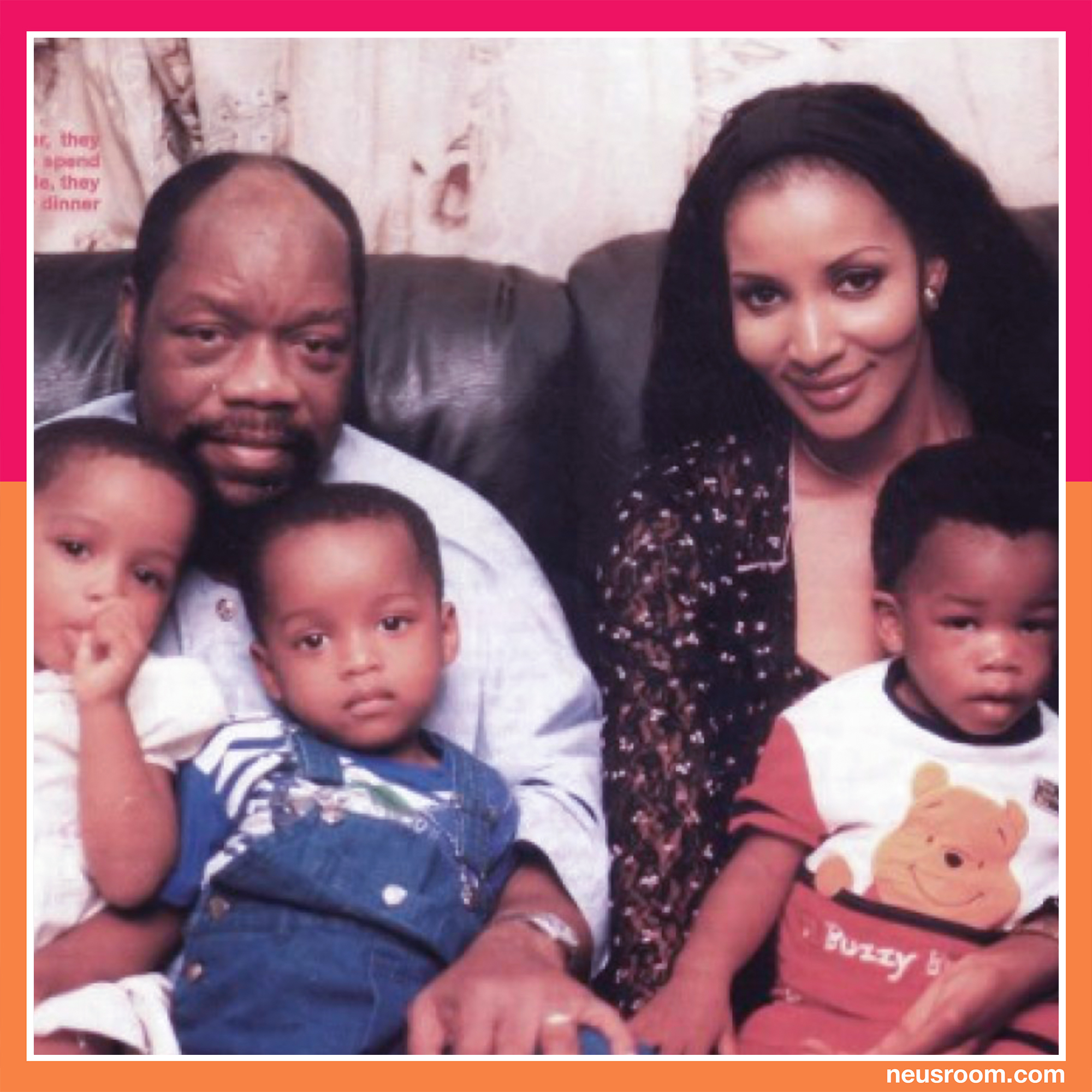

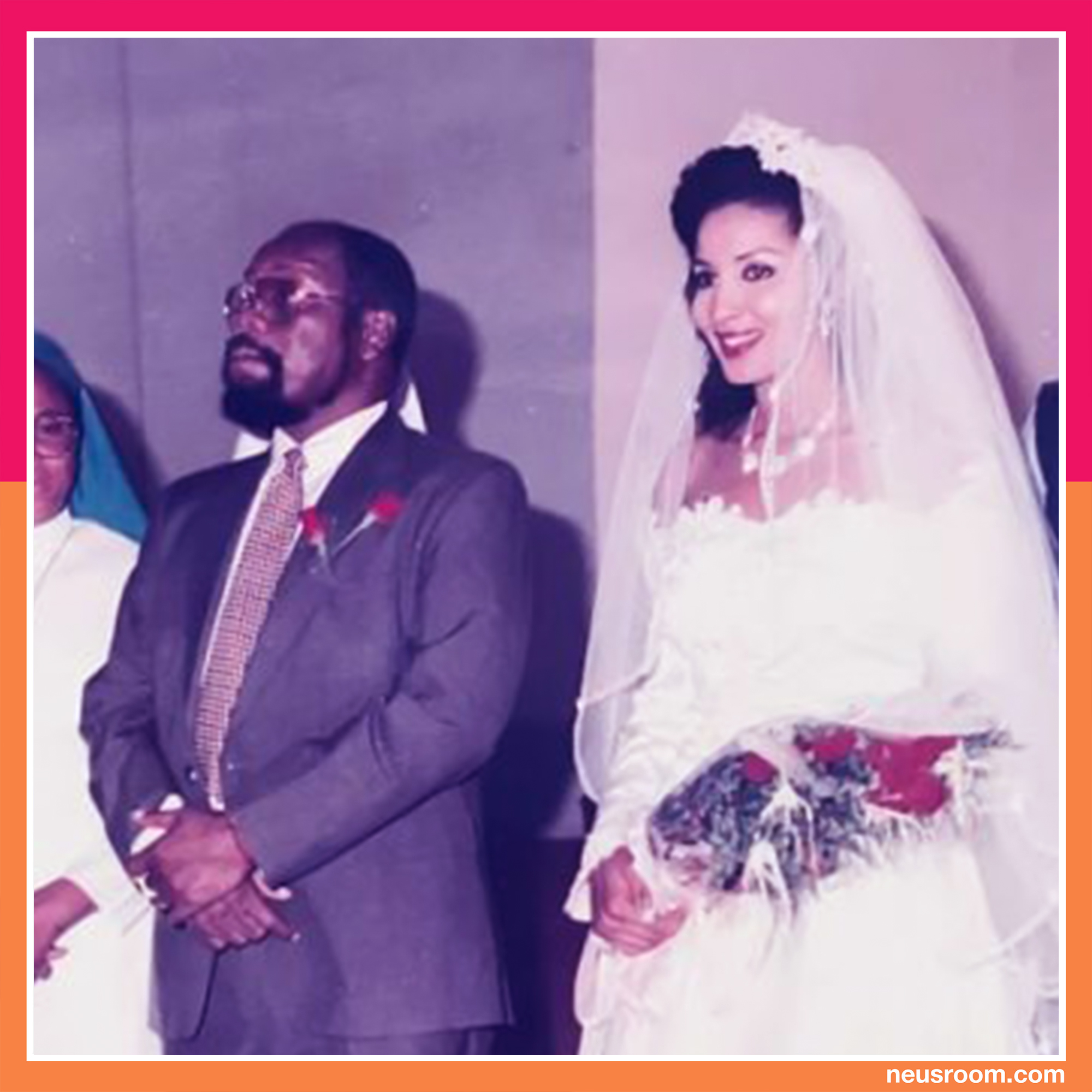

Ojukwu and his kids with his last wife Bianca, whom he willed his estate and all his money to, on the condition that she remains unmarried. Photo: Facebook/Bianca Ojukwu.

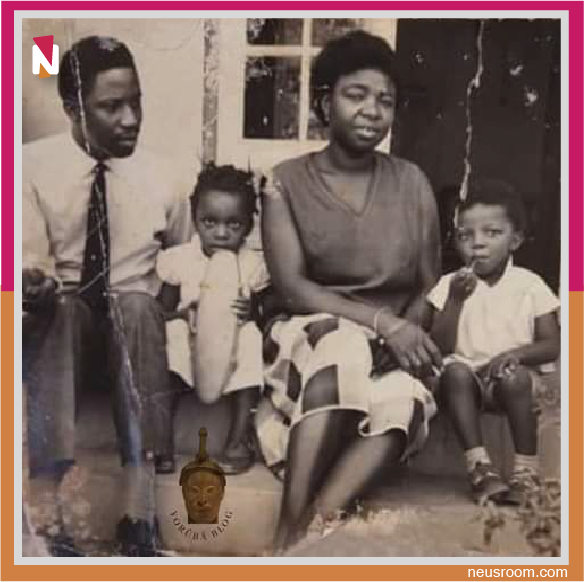

The brave General was not one without needs. Ojukwu enjoyed the company of beautiful women, and he married a couple of them. His first marriage in 1956 was to Elizabeth Okoli, who was said to be the daughter of Nigeria’s first indigeneous Postmaster General. The marriage lasted for two years as the couple separated in 1958.

Njideka Ojukwu, who left the Biafran General in Cote d’Ivoire and returned to UK.

Photo: vanguardngr.com

As the curtain fell on his union with Elizabeth, in 1964, Ojukwu married a single mother, Njideka Onyekwelu, who had earlier been married to a Ghanaian – Dr. Brodie-Mends. Njideka was the woman beside him during the civil war and they had Emeka Jnr, Mimi and Okigbo before the union crashed in Cote d’Ivoire when he met another woman while on exile with his family.

Asked what was the lowest point that tore their marriage apart, Njideka told The Nation newspaper in an interview in 2011: “it was in Ivory Coast. It was the conspiracy that eventually led to my leaving. It is better left for another day.” While in exile in Cote d’Ivoire, Ojukwu met Victoria.

Ojukwu and Stella his fourth wife were married for 10 years.

Photo: thenationonlineng.net

They were married till the early 80s when Ojukwu was granted a state pardon by the Nigeria government. He would later marry Stella Onyeador, who was Njideka’s chief bridesmaid during their wedding in 1964.

In 1994, Ojukwu, then 61, married his last wife – 27-year-old Bianca, a lawyer and beauty queen who won The Most Beautiful Girl in Nigeria pageant in 1988. Bianca was the daughter of late Chief Christian Onoh, a former governor of Old Anambra State, who vehemently opposed the marriage.

Ojukwu and ex-beauty queen, Bianca, got married on November 12, 1994 at Our Lady Queen Of Nigeria Catholic Church Abuja, despite opposition from the bride’s father. Photo: Facebook/Bianca Ojukwu.

Ojukwu died on November 26, 2011 in a London hospital after a protracted illness. In his Will which became a subject of litigation for allegedly favouring Bianca more than others, he listed Tenny Haman, Chukwuemeka Jnr, Mmegha, Okigbo, Ebele, Chineme, Afam and Nwachukwu as his eight children.

Ojukwu polled 1,297,445 votes in the 2003 Presidential election as APGA candidate. Photo: igbofocus.co.uk.

Before his death he ran for president under the platform of the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) in 2003 and 2007 but lost. The war may be over, but many Easterners are still peeved that the Nigerian authorities are trying to sweep the Biafran War story under the carpet over fears that it might incite another wave of bitterness and violence in some parts of the country.

“The Biafran war is still wrapped in a formal silence,” Chimamanda Adichie wrote in The New Yorker. “There are no major memorials, and it is hardly taught in schools.” She added that: “We cannot hide from our history. Many of Nigeria’s present problems are, arguably, consequences of an ahistorical culture.”