June 12: I Sat With The Father Of Richard Ogunderu, The Teenager Who Hijacked A Plane In 1993. Here’s What He Told Me

Neusroom’s Michael Orodare writes about Richard Ogunderu, the teenager who, alongside three other young men in their 20s, hijacked a Lagos-Abuja plane to protest the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election.

Written by Michael Orodare for Neusroom

12th June, 2022

“Imagine waking up early in the morning, and you couldn’t find your 19-year-old son in his room. He had left a message he was travelling to Jos. Then a few days later, his name was in the news across the world that he hijacked a plane?” Yemi Ogunderu told me on Monday, June 6, 2022, as we talked about his son Richard, one of the four young men who hijacked a Lagos-Abuja aircraft in protest against the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election.

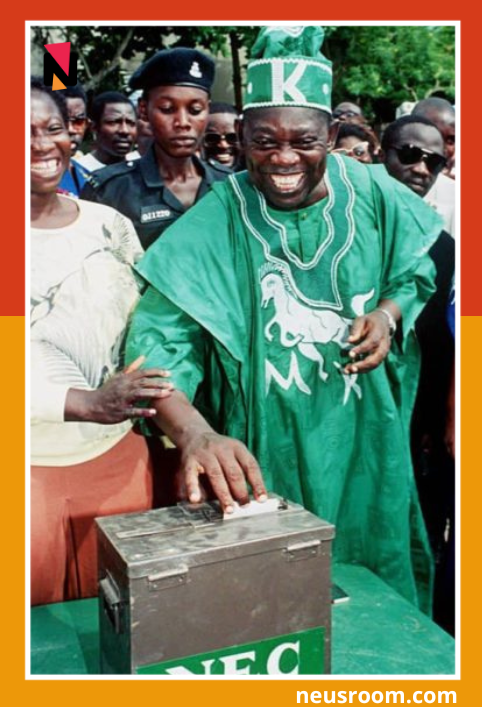

June 12! A day known as Nigeria’s Democracy Day is one of the most significant dates in Nigeria’s political history. On that day in 1993, Nigeria had a presidential election for the first time since the 1983 military coup, but it didn’t produce a President despite results showing Moshood Abiola of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) was leading his opponent Bashir Tofa of the National Republican Convention (NRC).

On June 23, the military ruler Ibrahim Babangida annulled the election result, and his action plunged the country into one of its biggest political crises ever. An interim government installed by Babangida on August 27, 1993, headed by Ernest Shonekan, failed to pacify the people.

An interim government installed by Babangida (left) headed by Ernest Shonekan, failed to pacify the people. Photo: PremiumTimes.

“I might embark on the programme of civil disobedience in the country. If those who make the law disobey it, why (should) I obey it? There is a limit to the authenticity one could expect from a military ruler who is anxious to hang on to power,” Abiola said in his reaction to the annulment.

With ‘Hope 93’ as his campaign theme, the business mogul, who had built a business empire in media, shipping, banking, aviation, oil and gas, among many others, assured Nigerians he was going to end poverty when elected, and he enjoyed nationwide support.

Abiola, a University of Glasgow trained Accountant, promised to eradicate poverty in Nigeria if elected President in 1993.

The annulment of the election sparked outrage across the country. Civil society groups, students and other young Nigerians led mass protests calling for the declaration of Abiola as the winner. The demonstrations, which ran for months, turned violent, with about 100 protesters reportedly killed.

“During one of our protests, soldiers attacked us around Eko Bridge, shooting at protesters and throwing dead bodies into the lagoon. I was shot in the leg and jumped off the bridge,” Abiodun Mustapha, who lost a leg in the protest, told me. “The soldiers also stormed the hospital where other survivors and I were receiving treatment and shot some of them on the bed. I escaped through the hospital window when the nurses rushed in to tell us the soldiers were trying to break in at the gate.”

The Hijackers

Richard, the second child and only son of his parents’ five children, lived with his father in Surulere, a highbrow Lagos neighbourhood that was home to many political figures and entertainers up till the late 1990s, while his mother lived in Jos with his sister.

He had just left secondary school in Ondo State and was planning to study aeronautic engineering. “There was no university in Nigeria offering that course, and I was planning to send him abroad to study after he rejected my suggestion to join the Nigerian Air Force,” his septuagenarian father told me.

Richard, full of life, a lover of good things and a fine dresser, violence was never one of his attributes. When he wanted to engage his father in a conversation about national issues, he taunted his father about how his generation was helpless about the country’s situation.

“He would tell me ‘you old men just sat there bemoaning your fate, won’t you do something about this country?’,” his father said.

His father described him as “strong-willed, obstinate and could be decisive over issues.” Richard has a broad understanding of current affairs, and you’d have to come up with a superior argument to convince him.

“He wasn’t a hardliner,” Ogunderu said. “Although occasionally you’ll see him complaining and condemning certain things he considered wrong in the society, his position on issues were not radical to the point of getting involved in such an action.”

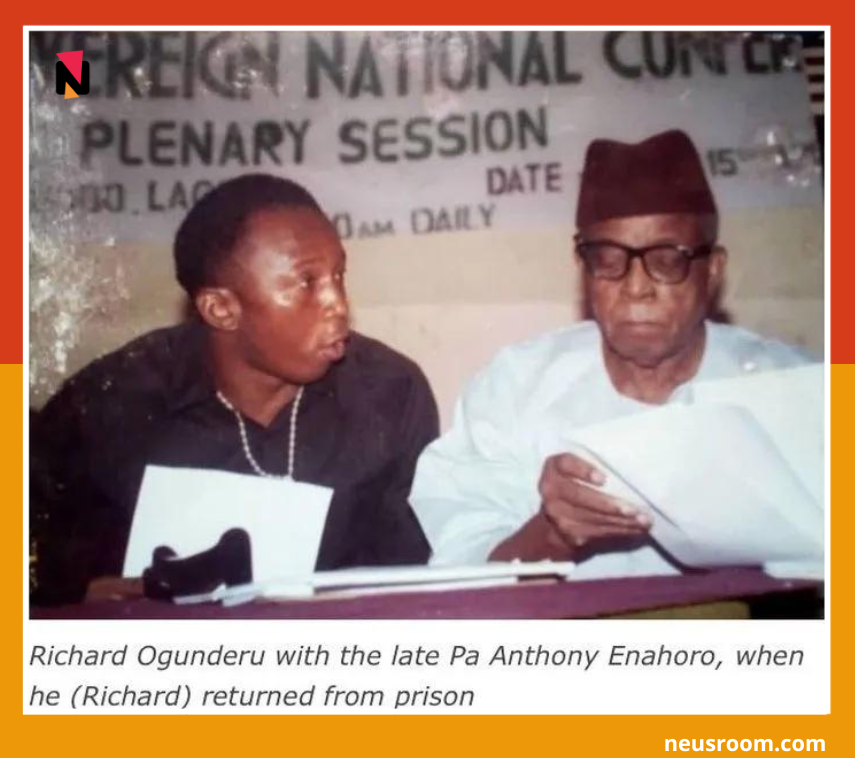

Richard Ogunderu: Full of life, a lover of good things and a fine dresser, his father said violence was never one of his attributes. Photo: Nigerian Tribune.

Richard took some of these traits from his father, who told me, “I used to be very heady, fearless and stubborn.”

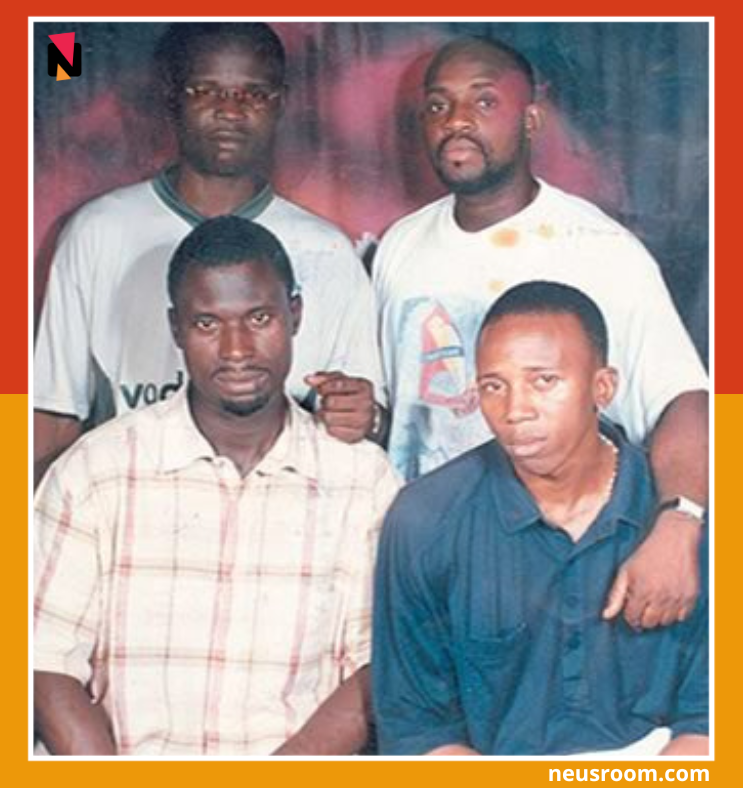

On Monday, October 25, 1993, amid the unrest that followed the June 12, 1993, election annulment, Richard and Kabir Adenuga, 22; Benneth Oluwadaisi, 24 and Kenny Rasaq-Lawal, 23; who were all members of the Movement for Advancement of Democracy (MAD), took a daring action that reverberated across the world.

They joined passengers in Lagos to board Nigerian Airways bus A310 aircraft flying from Lagos to Abuja. As soon as the flight cruised 30,000km above sea level, they held all passengers and crew members hostage with guns, which his father said security operatives confirmed were toy guns. They hijacked the plane and commandeered the pilot.

The plane sought to land in N’Djamena, the capital of Chad, for refuelling but was denied permission, then diverted to Niamey, the capital of Niger, where they planned to refuel and head for Frankfurt in Germany.

Niger, which borders Nigeria to the north, gained independence from France in August 1960, but France still wields influence on its politics and economy.

As soon as reports got to town that the plane had been hijacked, a statement was circulated. “They shared fliers on the flight detailing all their six demands,” Ogunderu told me.

Top among their demands is the announcement of Moshood K.O. Abiola as the president and the return of press freedoms in Nigeria.

Their action immediately made news headlines in local and international media. It was unprecedented in Nigeria’s history.

“Foes of Nigeria Rulers Hijack Plane to Niger,” a New York Times headline read on October 26, 1993.

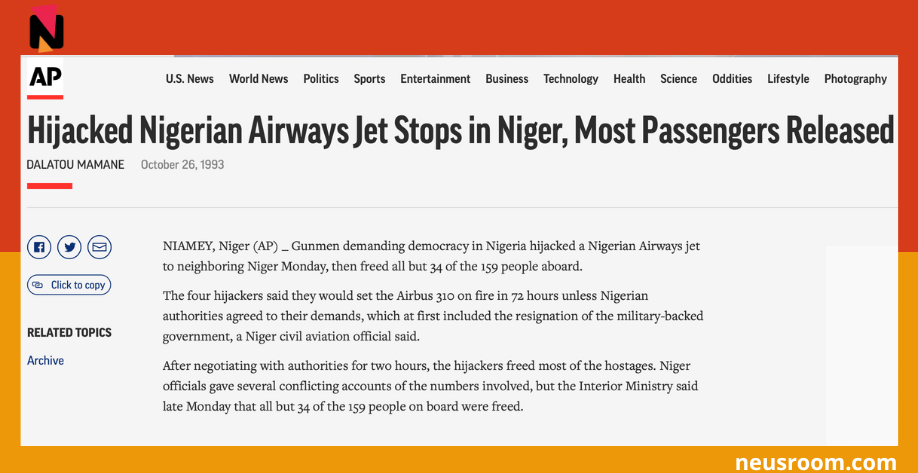

“The aircraft was carrying between 135 and 137 passengers,” the Associated Press (AP) reported.

Although some claimed Abiola had a hand in the plan, he denounced the action.

A headline of the Associated Press (AP) on the plane hijack.

The AP quoted Abiola as saying, ″We should do nothing that will be interpreted as a resort to the law of the jungle. I appeal to the hijackers… to end the hijacking.″

Monday, October 25, 1993

“I woke up that morning going to the toilet; his room was close to the toilet, I checked his room, and he wasn’t there. I asked Kunle (my friend’s son staying with us), and he said Richard had travelled to Jos. I was worried he travelled without telling me, but it was not his first time. His mother and sister stayed in Jos, so he often travels to see them,” Ogunderu said. “There was no mobile phone at that time to call them to confirm if he was in Jos.”

Later that day, when Ogunderu saw the news of the plane hijack on TV, he said, “I was one of those passionately analysing the situation. When my landlord at that time, Senator (Adetola) Ladega, said the hijackers could be Nigerians, I told him it was impossible. It is typical of the people of the Middle East not knowing my son was involved.

“Like many other Nigerians, I became sympathetic to their course when I saw their six-point demand. They were doing it to attract the international community’s attention to what Nigeria was going through at that time.”

Richard told The Nation newspaper in 2009 that his group acted because they were frustrated by the election annulment and needed to ‘send jitters down the spine of those in power.’

He said:

“Our action confirmed that when a system is inhuman, it could produce the extreme in all of us. A system that cares not, a system that does not listen to our cries and our woes, a system that wants to exterminate us does not deserve a day of existence.”

But Ogunderu said Richard never showed any sign of extremism. “The relationship between us was beyond father and son. We relate like brothers. I didn’t even know when he became a member of MAD. He had never discussed activism with me even though he knew I’m highly opinionated about socio-political issues.”

Ogunderu’s Arrest

After diverting the plane to Niamey, the group began negotiating with the local security operatives who had surrounded the airport.

They released the women and children on board on the first day after negotiating with authorities for two hours. A day after, they released passengers without links to the government, holding on to government officials as a tool for negotiation. The AP reports that Rong Yiren, the vice president of China at that time who was also on board, was released, while one of those held was the head of the Electoral Commission.

“The four hijackers said they would set the Airbus 310 on fire in 72 hours unless Nigerian authorities agreed to their demands, which at first included the resignation of the military-backed government,” AP reported on October 26, 1993.

According to Radio France International, the hostages were freed on Thursday, October 28, 1993, after Nigerian authorities ordered the aircraft to be stormed. The operation left one dead, a member of the crew (Ethel Igwe), and five injured, including one of the four captured hijackers. It turned out to be the youngest among them – Richard.

A New York Times headline on October 28, 1993.

At the time of the capture, the identity of the masterminds remained unknown.

“While this was happening, the leader of MAD, Mallam Jerry Yusuf, lodged in the hotel beside my compound, owned by my landlord, and we were both analysing the issue,” Ogunderu told me. “He knew my son was one of them and never told me anything. Until the day of my arrest, I knew nothing.”

The full scale of Richard’s action became clear to his father when he was arrested on the street of Surulere.

Ogunderu was visiting a friend in the neighbourhood on Thursday, October 28, 1993, when he was picked up by security operatives.

“While I was at my friend’s place, a few streets away, a young man came to me and said he saw some men around my house who looked like security operatives, and they were looking for Richard. I wanted to see the security operatives, but they advised me not to go,” he recounted. “Later that night, I decided to go and see my father, who also lived in Surulere. On my way, I was walking in an isolated place when they accosted me. I didn’t know the security operatives had lurked in the area and were trailing me.”

Ogunderu said while one of the operatives was trying to confirm his identity, “I told him I already know who he was; he should just tell me what the problem was.” A coaster bus parked, and they told him to go in. “I followed them. I didn’t know where they took me to because the bus was curtained round”.

When he saw Richard’s name in the newspaper, Ogunderu said “it was my rudest shock. It was like the entire world was collapsing on me. Photo: Kingsley Ofuonye

Ogunderu didn’t expect that being an observer without any links to the principal actors of June 12 could attract government attention to him. He was taken to an interrogation room where a team of intelligence officers from the Nigerian Army, Police, Navy, CID, and other security agencies led by one Col Mike Ndubuisi surrounded and questioned him about Richard.

“Immediately I got there, in the usual military-style, they just started asking ‘where is your son?’ I said is this how you treat your guest? Just barking out an order. I don’t know where I am, I don’t know how I got here; you’re asking about my son,” Ogunderu said. “Then they told me, ‘we don’t joke with people here. We ask the questions here, and you have to answer’. Looking around, I knew I was at a place where bluffing would not be welcomed.

“I asked them which of my sons, even though I know I have just a son. He said Richard, and I said to the best of my knowledge Richard left a message on Monday he was travelling, and I’ve not seen him.”

Ogunderu said he knew something had happened because Richard’s name was mentioned, but he didn’t expect it to be related to the issue in the country.

Richard and other group members “The Niamey 4′ as they were called. Photo: Twitter/Tolu Ogunlesi

“They questioned me further, asking how my son had left the house since Monday, and I didn’t know his whereabouts.” Ogunderu’s response to the question was that Richard was grown enough to travel, and it was not his first time.

“In the cell they kept me, I could hear the sound of the wave splashing water to the wall, but I didn’t know where I was.”

By the third interrogation, he said they left a hint about the reason for his arrest. “They deliberately left a copy of Guardian newspaper on the table, and all left the room.” When he picked the paper to read, he saw the report of the hijack with Richard’s name.

“It was my rudest shock,” Ogunderu told me. “It was like the entire world was collapsing on me. It was shocking in the sense that it was unprecedented in the anal of this country. Imagine a young man of 19 without prior military training, now giving to violence. We were so close that I couldn’t imagine anything like that could happen without me knowing. I know a lot of planning must have happened. I was caught completely unawares.”

Ogunderu said he was broken as a father when the initial report said two of the hijackers died. “To now learn that my son was part of it, at that time, it was a double tragedy. I later learnt that none of them died.”

More days of interrogation and detention followed, and he also met some passengers on the flight while in detention who spoke no evil of the boys.

Ogunderu said he didn’t know where he was until after 18 days in detention. “That was when I knew I was inside Bonny Camp. I was later moved to Alagbon, where I spent three days and was released after spending a total of 70 days in detention.”

When he was released, he was warned not to talk about the issue in public.

“As soon as I was released, I went to town, going from one newspaper to another, trying to connect those I could in the civil society groups,” he said.

His June 12 experience did not end after his release. He needed to visit his son and the other boys in Niger, where they were detained. He had also met the parents of the other boys, whom he said, just like him, had no prior clue about their children’s actions.

Ogunderu, who had never been to the Niger Republic before October 25, 1993, was filled with nostalgia and dread as he travelled to the West African country for the first time. He told me he couldn’t travel by air.

“For fear of being apprehended, I had to go by road,” he said.

The road trip from Lagos to Niamey via Kebbi state in northern Nigeria is about a 19-hour drive.

On his arrival in the French-speaking country, he connected with civil society groups who assigned him a representative that moved around with him and interpreted conversations in his meeting with government officials, including the country’s Justice Minister.

High Spirit

“When I met the boys, they were in high spirit,” Ogunderu said. “Richard told me all the boys involved just realised they have a common interest about the goings-on in the country, and they felt a sense of duty to do something.”

Ogunderu told me that Richard also clarified that their action had nothing to do with Abiola but the issue at hand at the time.

“The annulment drove them into taking action,” Ogunderu said. “To me, it was suicidal.”

Faced with the uncertain fate of the boys, Ogunderu said he doubled his effort on his return to Nigeria, meeting prominent people and politicians, and appealing to them to prevail over the government of France.

“No one could tell me what kind of fate awaited the boys, and I didn’t want to take chances,” he said. “If you’re conversant with the relationship between France and their former colonies, you’ll observe that the policy of assimilation was still very much manifested in their relationship. I took advantage of that, and it paid off.

“One of the things I pleaded for was that the boys should not be released to the Nigerian government because speculations were rife that they would be deported to Nigeria, and that would be too dangerous given the state of things then.”

By November 1993, General Sani Abacha had taken over government from Shonekan through a coup. His infamous regime recorded some of Nigeria’s most vicious human rights abuses.

Abiola (left) reportedly died of ‘cardiac arrest’ on July 7, 1998, a month after Abacha’s (middle) death. Photo: The Tableshakers

On June 11, 1994, when Abiola declared himself the winner of the election at Epetedo, Lagos, he was arrested on June 23, 1994, on treason charges and never made it out of prison. He reportedly died of ‘cardiac arrest’ on July 7, 1998 (a month after Abacha’s death).

Many pro-democracy campaigners, including Abiola’s wife, Kudirat, were killed during Abacha’s regime, while many others were jailed.

“The whole setting was so volatile,” Ogunderu told me. “I don’t think the Abacha government would have treated the boys with kids’ gloves.”

As Ogunderu requested, Richard and the other boys were not repatriated to Nigeria.

“The boys were retained in Niger, where they spent nine years in jail. They were not arraigned in any court while they were there. I think it was a strategy to keep them safe,” he said.

In Niger prison, Richard became a popular figure for organising tutorials for inmates.

“He established an education programme in the prison, which reduced crime rates. When he was released, the Niger people didn’t want him to return to Nigeria.”

While all these lasted, Ogunderu said the event displaced his family and ‘cost the family a lot’.

“I had to watch my movement for a long time because I didn’t want to be picked up again. The landlord, Senator Ladega, a first Republic Senator who was in his 70s, was also arrested. The house was constantly being troubled. We had to change residence for my good and the family,” he said.

“What was more important then was my son’s life and other boys’ lives. I couldn’t afford to sit in a place while my son’s life was in danger.”

Richard and his colleagues returned to Nigeria in 2002 after the transition to democracy and have maintained a low profile.

Looking at how far Nigeria has fared with democracy since 1999, Ogunderu said the agitation “wasn’t worth it”.

Although he told me Richard wasn’t available to speak with me, he told me Richard regrets returning to Nigeria.

Like Ogunderu, other June 12 activists like Abiodun Mustapha who lost a leg during a protest, and Akin Orisagbemi, one of Kudirat Abiola’s aides shot at the Abuja High Court during Abiola’s trial in 1994, told me the transition to democracy and changes in power from 1999 has done little to alter how Nigerians lived and experienced power.

The retarded progress, development and lack of respect for the rule of law, which inspired Richard and other young people’s justifiable anger towards dictatorship and systemic corruption, and a desire to fight for a better society in the 1990s, is still prevalent 29 years after they challenged the establishment in an unprecedented way. This lack of progress also led to the EndSARS protests of October 2020 and made it a global phenomenon that has ignited an unusual political consciousness among young Nigerians.

“Democracy is beautiful,” Ogunderu told me. “If it’s about that, I’ll say their effort has been productive. But if those boys had died just like their mentors and we still find ourselves here, I wouldn’t say it was worth it. Many people have remained deformed due to confrontation with security operatives back then.”

Brilliant writeup ,well detailed research work and attributes.

Thumbs up

Well detailed. I didn’t even know something like this happened. I think I was too young then. I only knew there was an election that was annulled, which was followed by civil unrest.

Wow👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽 Very Enlightening

Good job 👍 from this Journal

My kind of journalism. Detailed, deep, factual and well researched. Kudos Mr Orodare.

I really enjoy this piece. The article was well detailed and I must commend the writers effort in putting all this together.

Journalism at it’s peak.

great report. so much enlightened.

This is enlightening. Nice research and great write-up.